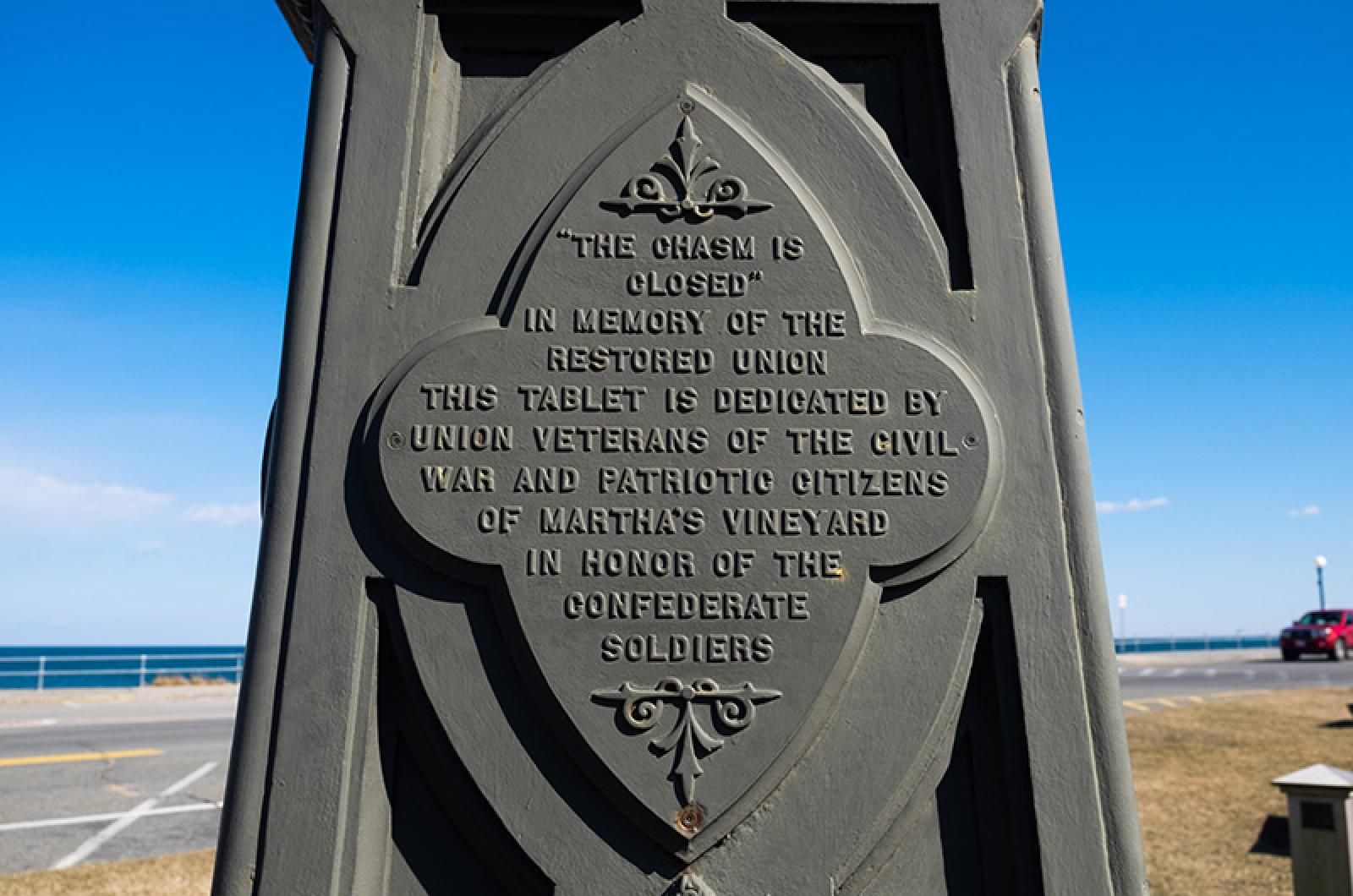

Four and a half years ago, I took to task the Martha’s Vineyard NAACP over a matter that goes to the heart of the organization’s work. I insisted it demand the removal of two plaques honoring Confederate soldiers located in a public park, maintained on the public’s dime in Oak Bluffs.

The plaques added insult to injury, I told the group at a March 2019 chapter meeting. And I warned them that to remain silent on the issue would make a mockery of its mission: “The Advancement of Colored People.”

The group heard me and agreed to demand that the plaques be removed immediately by its owner, the town of Oak Bluffs. The group, however, insisted on one caveat. Instead of tossing the markers, lawyer and then-MVNAACP executive committee member Arthur Doubleday wanted them donated to the Martha’s Vineyard Museum for their instructional value. The institution could better put things in historic context, Mr. Doubleday said. Three heated select board meetings later, and after a lot of press, the select board followed the chapter’s lead.

The plaques came down.

But whether the museum has been effective in putting things in historic context is another matter.

Last month, I made my way to the Island as I do every summer, this time meeting with Martha’s Vineyard Museum executive director Heather Seger. I followed her to an outbuilding behind the main museum, where the plaques and a brief explanation were relegated to a darkly-lit wall in the corner of the former barn. Ms. Seger assured me her team, including research librarian Bow Van Riper, had created a more comprehensive and robust exhibit online.

What I found there, however, was thin at best and less than contextual. At 30,000 feet, it failed to tell the whole story.

Let’s face it: one can’t talk about the Oak Bluffs Soldiers’ Memorial Monument, where the Confederate plaques were located, without talking about the Civil War. And one can’t talk about the Civil War without talking about slavery. And one can’t talk about slavery without talking about the institution, not piecemeal, but at 30,000 feet. Put another way: the story can’t be isolated to the South and its obsession with Black bodies and the free labor they produced. We have to also talk about the blood of the institution staining the hands of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts and, indeed, New England.

To be sure, exhibit visitors need to come away clear on a few things. That Massachusetts, the first state to abolish slavery, was also the first to legalize it. That long before “Cotton was King” down South in the 1800s, Martha’s Vineyard and Massachusetts were importing enslaved Africans dating back to the 1600s. That by 1776, dozens of enslaved Africans were still working in bondage on the Island. That the colony’s shipyard built the vessels that transported us. Its distilleries produced the rum that incentivized our capture and sale. Its waters and fisheries produced the cod that sustained us as an investment. Its textile mills clothed us for the fields and our sale on the auction block.

And it doesn’t stop there.

One need only visit nearby Newport, R.I. — a short 39 miles away from Martha’s Vineyard by boat — to find God’s Little Acre, the largest intact colonial burial ground of enslaved Africans in the country.

Fourteen miles north of it sits the town of Bristol, home to the DeWolf family, the country’s largest and wealthiest trafficker of enslaved Africans in American history. It’s the same family that intermarried with the Colts, producers of one of the most important tools to facilitate the transatlantic and domestic trade of our people — guns.

And yes, museum visitors should be clear that Black history icons such as Prince Hall, Phillis Wheatley and Elizabeth (Mum Bet) Freeman weren’t enslaved in Virginia, the Carolinas or Georgia, but in Massachusetts.

Indeed, it’s time to stop stigmatizing the South, the Charles Strahans of the world and his compatriots, out of convenience. Time to stop the hypocrisy of promoting the false narratives that suggest only folks below the Mason Dixon line engaged and profited. Instead, Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts and New England must fully own its history of slavery in all of its inhumanity, especially as we navigate the issue of reparations.

Everybody — but especially Black folk — visiting the museum’s exhibit needs to come away clear that Martha’s Vineyard wasn’t always the summertime sanctuary of colored folk or the playground of the so-called Black elite. That unlike artist Lois Mailou Jones and writer Dorothy West, who the museum has curated exhibits around, you can’t put a bow on some stories. Our children need to know our time on Martha’s Vineyard didn’t start with the tent rivals at Oak Bluffs. Or fishing charters at Menemsha. Or lighthouse visits at Aquinnah. Or Greek Week. Or presidential compounds at Katama.

First came slavery. And slavery by any other name is still slavery.

So, let’s resist adulterating and abridging what happened. Otherwise, Martha’s Vineyard becomes as guilty as Ron DeSantis and Florida in coloring and corrupting history. Remember that only after sharing the truth can we reconcile. Only after exposing the theft of our labor can our children understand white wealth and the debt owed.

Tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. Do it because it’s the right thing. And do it now. Thank you.

Clennon L. King is a journalist, filmmaker and historian. He lives in Albany, Ga.

Comments (6)

Comments

Comment policy »