Clearly, I have a propensity for islands. I have lived on Manhattan Island. I have lived on the Vineyard for decades and known it all my life. Now, leafing through old newspaper articles I have written, I am reminded that in the 1960s, soon after Alaska became the 49th state, I was offered the possibility of a long stay on Shishmaref, a five-mile long, mile and a half-wide Alaskan Inuit (in those days, Eskimo) island.

I had talked the Providence Journal, where I then worked, into sending me to Alaska.

All over the new state, I talked with firemen and policemen and hunters, public health nurses and Inuits. I learned that our new largest state — in those days before we were conscious of global warming — had a glacier larger than the state of Rhode Island.

I was also told about the big game hunts in Alaska, where hunters came from everywhere to kill the now-endangered polar bears. And I was told of Jim Lenz, one of Alaska’s 64 licensed polar bear hunting guides.

A former Flying Tiger and Pacific Northern Airlines pilot, Jim had been leading such hunts for a decade. I didn’t want to hunt polar bears, surely, but I did want to see a remote part of Alaska. I was told Jim Lenz could fly me anywhere.

“When Jim Lenz flies, God flies with him,” I was encouragingly told.

So I found him and asked him to fly me to Shishmaref. He delivered mail and necessities there each week and he agreed to take me.

Shishmaref, it turned out, was near Little Diomede, an American Inuit Island within sight of Big Diomede — a Russian Inuit island. The year before my visit, a Russian Inuit had walked out on the ice from Big to Little Diomede. Since then any unexpected visitor to an American Inuit island had been suspect.

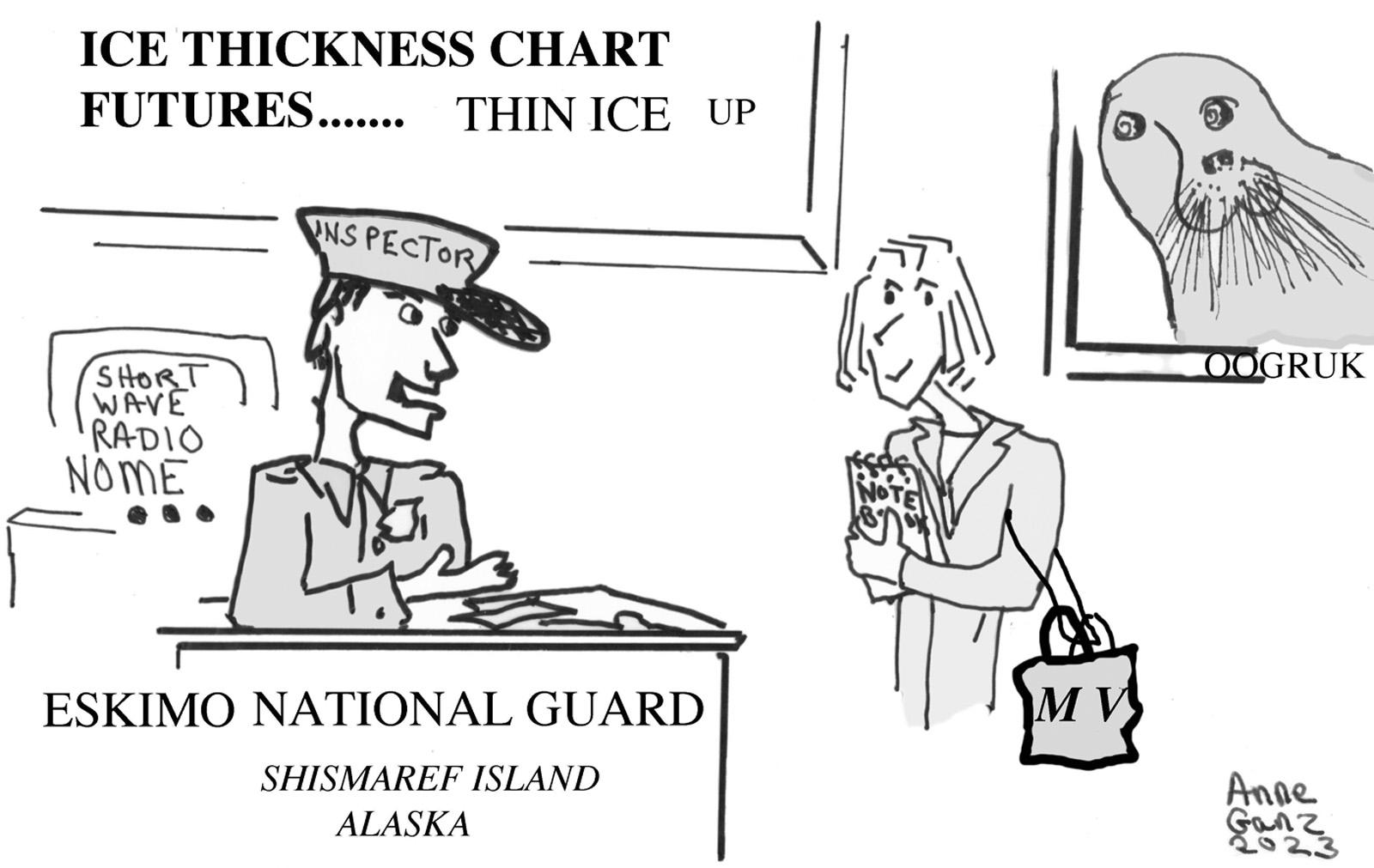

When I stepped off Jim Lenz’s plane, an Inuit National Guardsman was quick to greet me. He told me I could go no farther than his office until he had radioed National Guard headquarters in Nome. He had to know my name, what outfit I was from, and why I was there.

I said I was an American journalist and surely not a Russian spy. But he kept me in his office while he awaited clearance from Nome.

Finally, I was allowed farther into the island’s village of 200. There I met a few Inuits and the non-Inuit Lutheran minister and his wife. I was taken inside the church and the school, the post office and the general store. The rusted barrels outside, I was told, contained heating oil that came in by boat. Water for residents came from melted ice.

To get to the village center, we walked past clotheslines of drying oogruk — bearded seal meat — and sled dogs tied to stakes, and through backyards of boat motors and empty ginger ale cases.

A few kinds of wild berries, I was told, grew on Shishmaref, and there were whitefish and herring to catch in the river and seal meat of one sort or another. But most food had to be flown in.

I was told of winter polar bear hunts as far out on the ice as 20 miles. One had to go way out to open water to get to polar bears.

April and May, I learned, were seal and oogruk-hunting times. Then both animals would climb out onto the ice. The seal skins were used for clothing, the meat dried and eaten all winter. Some skins were cleaned and turned into pokes — bags to hold berries preserved in seal oil.

At the end of my visit — by then quite certain I wasn’t a Russian spy — I was cordially asked by the National Guardsman if I would like to return and perhaps stay for a while. He was sure he could find someone to put me up. Island-lover though I am, I declined and flew quite happily away with Jim Lenz.

I probably thought then and surely think now, that Vineyard winter snows are quite deep and cold enough for me. And I clearly remember my sample bites of oogruk on Shishmaref. They were, I hoped, a once in a lifetime experience.

As for native berries preserved in seal oil, I was certain then and now that Vineyard wild blueberries fresh off the stem are tastier.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »