It is tough to imagine the mindset of the first farmers, those pioneers of biological engineering who, consciously or not, began bending wild flora and fauna to human ends. It is so tough to imagine, in fact, that experts in the field have yet to reach any consensus, and the origins of agriculture remains a topic of heated debate among anthropologists.

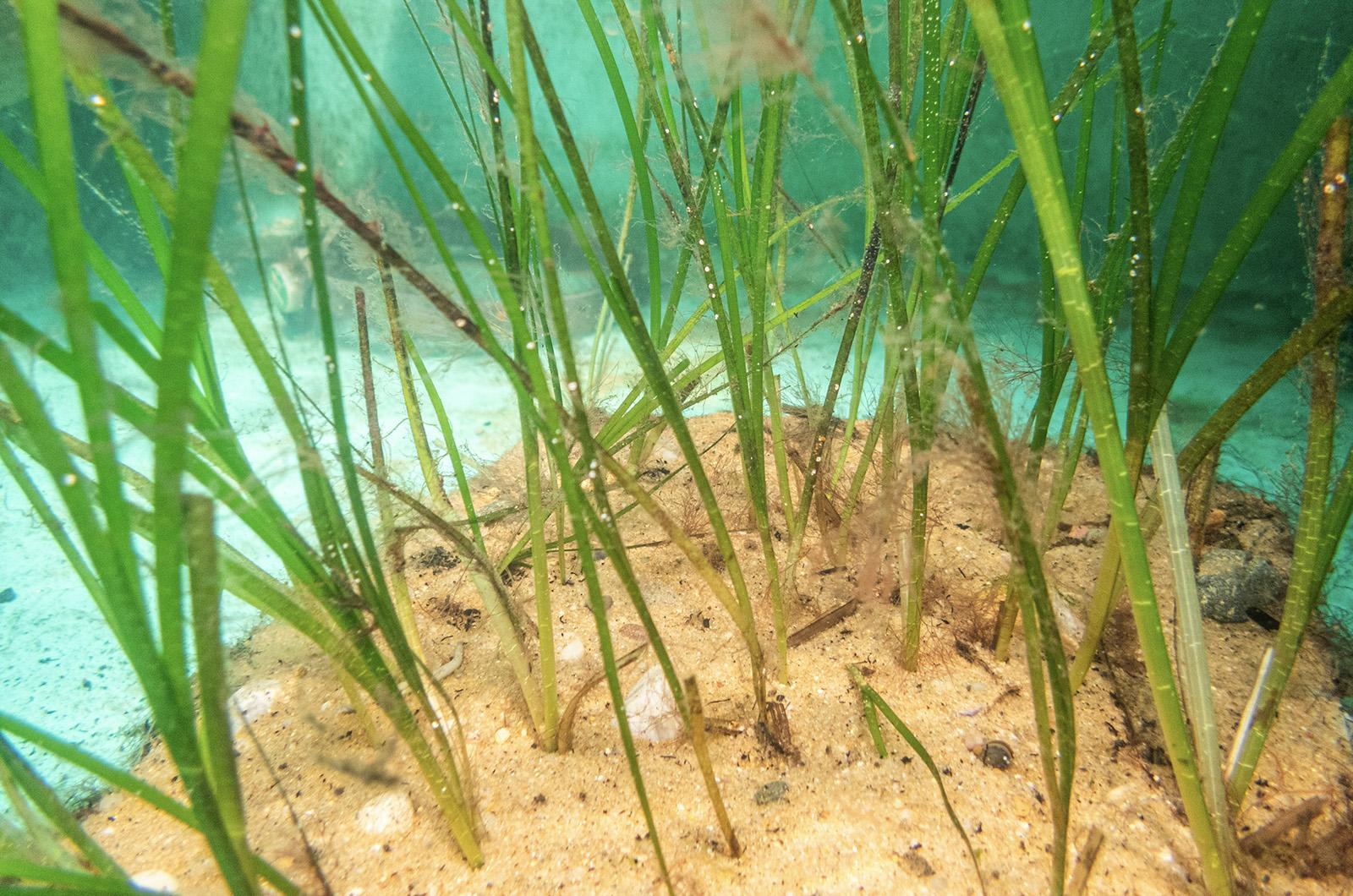

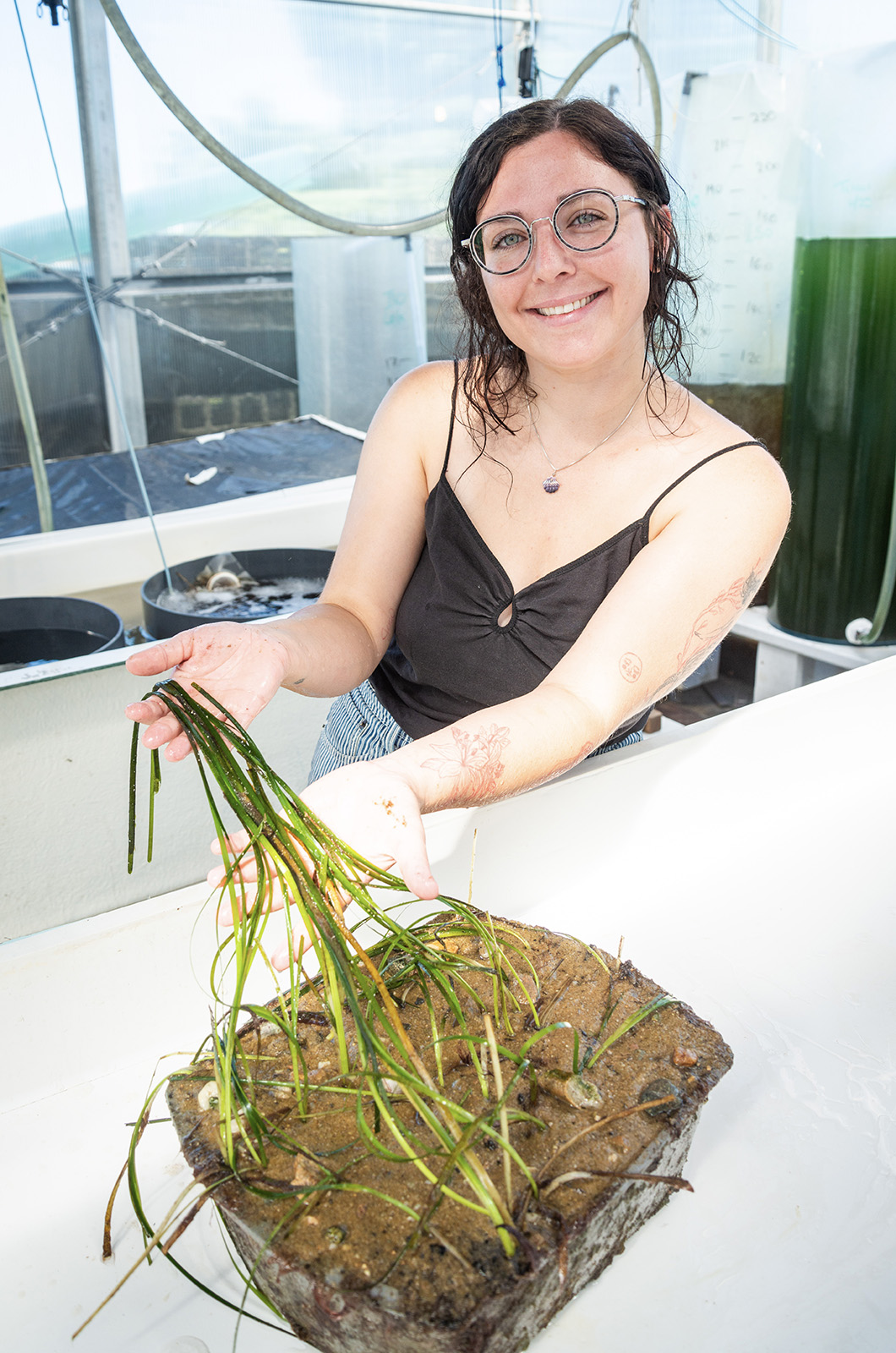

On-Island, however, we have a front row view of such a process, though the methods used today doubtless differ greatly from those of our ancient ancestors. For example, in a greenhouse at the edge of Lagoon Pond, in a plastic tub speckled with several shellfish species, the Island’s first crop of human-cultivated eelgrass flourishes.

It has been a three-year journey to get to this point, said Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group eelgrass restoration coordinator Alley McConnell.

“The first year, I mostly came away knowing what not to do,” she said.

Eelgrass is not a conventional crop, nor part of a traditional agricultural system, so it may take some convincing for the reader to view it in an agrarian context. Thus, a digression on bay scallops is in order.

The Vineyard does have wild bay scallops, but that population is heavily supplemented by hatchery-grown specimens, cultivated by both the Shellfish Group and town shellfish constables. Rick Karney, former director of the Shellfish Group, once described the strategy to me as “scallop ranching,” raising them young before releasing them to graze in the wild.

If scallops are cattle in this analogy, then eelgrass meadows are pasture, the environment in which scallops frolic. The analogy is not perfect, however, as eelgrass is not food for the scallops, but rather serves as their protection.

“When they are young, they have byssal threads, little sticky threads that let them stick to the grass,” Ms. McConnell said. By attaching themselves to eelgrass, the scallops can avoid aquatic predators and gain access to more food higher up in the water.

And so, to improve the lives of these aquatic cattle, and gain all the other environmental benefits eelgrass can provide, Ms. McConnell has embarked on a mission to grow and restore eelgrass in Island ponds.

Though other eelgrass restoration projects are taking place across the East Coast, Ms. McConnell said, few others have taken the step of cultivating the species. Instead, they have mostly depended on harvesting wild eelgrass from healthy meadows and transferring it to restoration spots.

“There’s nowhere on the Vineyard I really feel comfortable doing that,” she said. “It’s not flourishing tenfold anywhere.”

The primary challenge for eelgrass growing, both in wild and laboratory conditions, is eutrophication, the process by which nitrogen pollution (largely from septic and fertilizer runoff on-Island), causes fast-growing algae and seaweed to proliferate faster than normal.

Those fast-growing organisms attach themselves to individual eelgrass blades, covering them up enough to prevent photosynthesis. In the lab, where eelgrass is grown in filtered seawater, Ms. McConnell must clean the blades weekly.

In terms of its growing process, eelgrass is quite like a conventional crop, since it evolved from terrestrial grasses. It is one of the few underwater flowering plants, releasing pollen into the water to fertilize other plants and produce seeds. Those seeds, in turn, are harvested and planted by Ms. McConnell, in underwater pots filled with course sand and peat moss.

The grass takes two-years to reach maturity before it begins to flower. Just this year, Ms. McConnell said, they achieved their first in-hatchery eelgrass flowering, which she said is the first-time flowering eelgrass has ever been achieved in an artificial setting.

But while eelgrass agriculture grows in leaps and bounds in the lab, Ms. McConnell said, efforts to restore it in habitat remain embryonic. Restorations have begun in Menemsha Pond, but much of the Island’s coastal watersheds remain too nitrogen-polluted to support a restored meadow.

In the meantime, Ms. McConnell is building her skill set, recently having received a Martha’s Vineyard Vision Fellowship to visit and learn from other restoration projects across the coast.

“When that time comes, the shellfish group will be ready. We will be there to restore eelgrass,” she said.

Comments

Comment policy »