I am driving with my son Hardy on I-95 south, headed for our first college tour. Hardy is 17, a senior in high school. He is taller than me, he shaves, his deep voice still surprises me. He is a young man now and yet when I glance at him seated in the passenger seat I can still see the baby he once was. Sort of.

I have heard the college tour trips can be beautiful bonding experiences, that these long drives with the future firmly planted center stage are ripe for deep talks about life and growth and the passing down of generational knowledge. But the only thing I can think about at the moment is my funeral.

“How about the Vangelis score from Chariots of Fire,” I suggest, referring to the stirring music to one of my favorite movies. Hardy and I first watched it together when he was about eight years old at 3 a.m. I couldn’t sleep and was up late watching TV. Hardy couldn’t sleep either, he could never sleep as a little kid, and he had joined me on the couch. He seemed to like the film, which surprised me — a slow moving story about four UK runners preparing for the 1924 Olympics.

“Opening or closing?” Hardy asks.

“What?”

“Do you want the music to play at the beginning of your funeral service or the end?” he clarifies.

“Oh, the beginning, definitely,” I say. “That way everyone will be imagining youth and potential glory. That sort of thing.”

“Got it,” Hardy says, pretending to write this information down in an imaginary notebook.

I am not sick and so these funeral arrangements are not pressing. But it’s a long drive and I can’t help where my mind travels. Hardy wanted to drive but I wouldn’t let him. He is a good driver and has highway experience but something about this type of trip made me want to sit in the driver’s seat. It is an illusion of course, that I am still in control of the direction his life will take, a role I have become perhaps too comfortable with. But I can’t help myself.

He retaliates from the passenger seat by telling me about the horrors of the world, reciting news events and statistics about the terrible realities of the human condition.

This is how we roll, making funeral arrangements for me while also growing somewhat depressed about the sorry state of the world. And as we continue down the road, I think about how much I will miss this.

•

We pull up to the university, find parking, and get ready to take the official tour. We are at my alma mater and I had been excited to show Hardy around. But being here feels like I could be at Anywhere University. I don’t connect, seeing it now through my son’s eyes. The past has been swallowed by the future and I walk mutely through the tour, listening to anecdotes from the guide but mostly distracted as I think about all the things I have not yet taught my son — the fade-away jumper or how to drive a stick shift.

During my wife Cathlin’s pregnancy I became obsessed with all of my loose change, desperate to gather my pennies into rolls (this was before coin counters showed up in banks). If I could just coordinate my change before he was born, I thought I would be ready for fatherhood. Now I think, if only I can teach my son to throw a tight spiral I will be ready for him to leave me.

The tour guide says something funny and everyone laughs. But now I am back in the delivery room and then home from the hospital, trying to figure out with Cathlin the enormity of what we don’t know about raising a child — which is basically everything, including how to keep him alive.

Hardy was born with a muscular condition in his neck called torticollis, a long word that basically means there was an injury in utero to his neck so that he had trouble moving his head. But it wasn’t obvious at first. Neither Cathlin nor I noticed it, just like we didn’t notice he wasn’t nursing properly — that he couldn’t latch on to Cathlin’s breast and actually take in milk. We only noticed he cried a lot and seemed to be getting thinner.

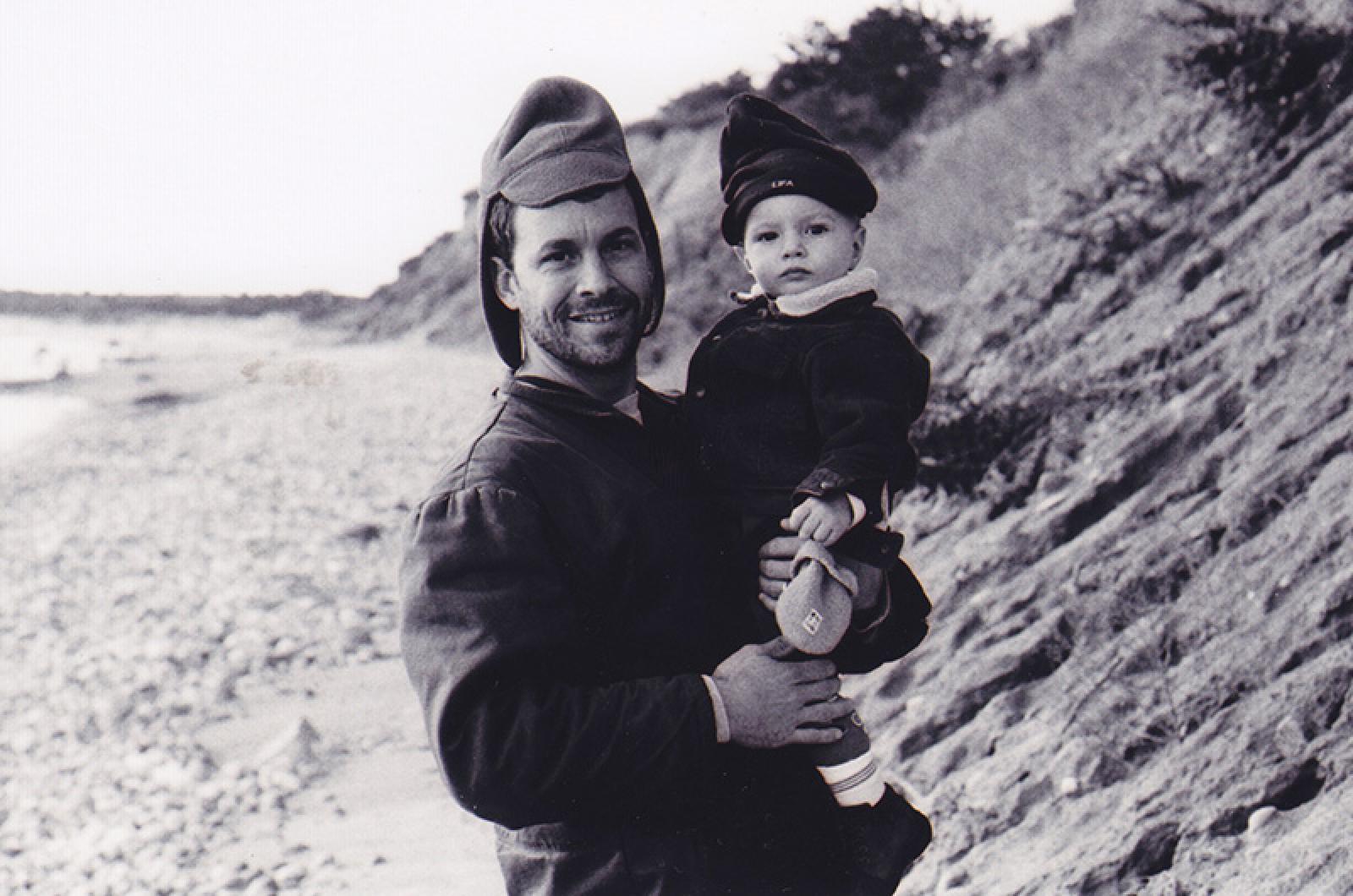

We were living in Tallahassee, Fla., at the time, far away from family and friends, the type of community who could have passed down information and lessons, who could have told us our child was starving. I have photographs of those early days, like all parents do, but it is so hard to look at them now, stills of Hardy struggling desperately to tell us he needed help. In one photo his little hand is raised in a fist as he lays back on the bed wearing only a diaper. This power symbol is offset by a scowl and bony ribs.

Eventually, Cathlin and I did figure out what was wrong and we learned how to feed our son. But the memory of those days and our ignorance haunts me still.

•

After the tour, Hardy and I look for a place to eat. We settle into a small restaurant but instead of talking to my son about his future I realize all I want to talk about is our past together.

Soon after Hardy was born I became obsessed with baby sign language, something I had read about in one of the many parenting books I devoured in the early days. We started when he was about seven months old, when according to the books a baby’s mind is capable of communication but that the physical elements of language are still many months away. But I was not satisfied with a few elementary signs like I saw some of the other babies doing down at the playground — banging their small fists together to ask for more or making a small circle with their thumb and forefinger to ask for a Cheerio.

I started by flapping my arms every time I saw a bird and eventually Hardy caught on, moving his arms up and down whenever a pigeon flew by. We lived in New York city then, so this was a constant occurrence.

Then we moved on to more animals (bear, chicken, gorilla, elephant), verbs, and eventually the near equivalent of sentences. I want (pat the chest) to go outside (turn an imaginary door knob) to see the squirrels (pretend to nibble an acorn). Soon we were like a couple of first base coaches, flashing our signs to communicate even when standing far away from each other.

Hardy has heard this story many times, but as I tell it again over dinner I understand more fully that he has no actual memory of those moments. It is more second-hand knowledge, an as told-to-him memory. It strikes me then that this is the way it will be for me next year, learning about his life through phone calls and visits home rather than being there in the moment.

I feel a chill run through me and suggest we take a walk. I show him a few of my old dorms, pointing to windows I once looked out from, wondering where my life would take me. And then it is time to drop him off with an undergraduate I know, who will take him out for the night, to show him what college is like outside of the classroom. We talk for a bit but I quickly feel like a third wheel.

“Don’t go crazy,” I say to Hardy and then I am off, walking out of sight and looking for a place to sit down and collect myself. Next week it will be Cathlin’s turn to take Hardy on a college tour. When she returns she will tell me how unmoored she also felt, and we will sit together on the couch, holding hands and being quiet. But tonight I am on my own.

I see another mom and daughter I met briefly on the tour. We smile and wave but do not talk as they are enclosed in their own bubble. Instead, I think back to Hardy and our sign-language days, and to next fall when Cathlin and I will drop him off at college. I can see it now, that leaving moment, when he has turned away and I am standing there wondering what to do with my hands. And then I will shout to him, hoping desperately that he turns around so I can flash every sign I know to tell him how much I love him.

But if he is anything like I was at that age, he will be too busy moving forward to look back. And that is exactly how it should be.

Comments (31)

Comments

Comment policy »