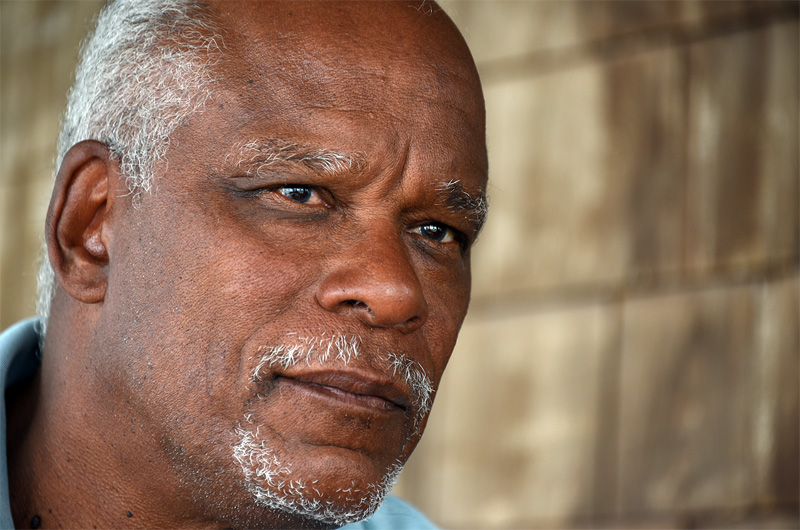

For documentary filmmaker Stanley Nelson, his latest project, Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities, has been a long time in the making. For the past 15 years he has written proposals and conducted research for the documentary. But the film has even deeper roots. Mr. Nelson’s mother attended Talladega College, a historically black college in Alabama. Mr. Nelson’s father attended Howard University.

“My father... really would not have gone to college if it hadn’t been for the fact that Howard University was right there,” Mr. Nelson said during an interview at his Oak Bluffs home, sitting on a porch overlooking Inkwell Beach. His father bought the house 50 years ago, and the family traveled up from Washington D.C. each summer to visit.

“There he was really nurtured, which is a part of what black colleges were and still are. He had professors who told him you’re really smart, you know, you should stop goofing around, and that was the first time he’d ever been told that in his life.”

He continued: “My mother and father both went to HBCUs [Historically Black Colleges and Universities], and so HBCUs changed their lives, which changed my life and my siblings’ lives, and my kids’ lives, and their kids down on through the generations.”

Tell Them We Are Rising tracks on an institutional scale the trajectory of historically black colleges and universities from their inception to present day. The film sets the stage for their development in antebellum America. In a featured interview, Marybeth Gasman, a professor of higher education at the University of Pennsylvania, said: “There was another type of brutality that took place during slavery, and that was the brutality of ignorance, keeping intellectual thought, keeping learning, keeping reading, keeping knowledge from slaves.”

During the Civil War, some who fled to freedom in the north learned to read at contraband schools, so named for the term given to escaped slaves. After the war, the American Missionary Association, and later the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the federal government, created schools for African Americans. Over 86 black colleges existed by the late 1800s. At the outset, these institutions were subject to debates over educational philosophies. The film explores ideological differences between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois as an example.

Through the film’s accounting of the creation and rise of historically black colleges and universities, a broader theme emerges.

“We felt that part of the throughline was this bigger story of HBCUs role in pushing forward equality and change for African Americans,” Mr. Nelson said. “The sit-in movement could only have started at HBCUs. Brown vs. Board of Ed., the suit for equality, could only have happened at HBCUs. It wasn’t going to happen from Harvard. Who’s going to start it? The sit-in movement started with four black students at North Carolina A&T saying, ‘This is ridiculous, let’s just go out to Woolworths and sit there until we can be served. We can’t even go to eat in the town where our school is.’ And that started a whole movement across the country.”

Mr. Nelson acknowledged that there were many other avenues the documentary could have explored, including the role of sports or fraternities and sororities at HBCUs. It touches on these elements in brief. The emphasis on the historical rise of the institution of HBCUs was partly driven by Mr. Nelson’s realization that these colleges and universities have vast, underutilized archives.

“We really felt that there was this whole treasure trove of still pictures that hadn’t been seen, and that were really different than what you normally see about the black community,” he said.

Mr. Nelson added that this approach meant the film was created during the editing process. It is composed largely of archival photographs and film interspersed with interviews with historians and HBCU graduates. Over 75 sources contributed stills and footage, ranging from the National Archives and Library of Congress to families who responded to a call for photographs with personal snapshots.

While the project is primarily retrospective in its focus, it ends at the present moment and the current challenges facing HBCUs. Morris Brown College, a historically black college that lost its accreditation in 2002 and went from serving 2,500 students to just 50, exemplifies the issue. Mr. Nelson attended Morris Brown for one year during a path through college that started at NYU and ended at City College of New York.

“That was especially poignant to see Morris Brown and the chains on the oldest building on campus, the overgrown grass and the burned out buildings,” he said. “That’s something that you don’t expect. You expect these institutions to always be there, you know, because they have these campuses and everything. For it to be not there was just amazing. So we wanted to tell that as part of the story.”

Concerns facing HBCUs about enrollment, funding and accreditation are magnified under the current administration, he said. “HBCUs have been in the news more during the first few months of the Trump administration than they have been in decades,” Mr. Nelson said, referring to both unfulfilled overtures and potential threats to HBCUs posed by the administration.

In this tumultuous time, Mr. Nelson emphasized the importance of black colleges. “Until this country gets rid of racism, we’re going to still need HBCUs, and we don’t seem to be getting any closer to ending racism. We seem to be getting pulled further and further away.”

And though some HBCUs are struggling to maintain viable enrollment statistics, partly because desegregation opened up previously unavailable educational options to black students, Mr. Nelson cited the “Missouri effect,” noting that some have seen an uptick in enrollment following racial incidents at the University of Missouri in 2015. Some students, he said, are deciding: “I want to live four years of my life where I don’t have to deal with racism.”

He continued: “It’s a black intellectual space, it’s a space where you have young African Americans who can talk about their problems, talk about change, discuss these kinds of things in a way that’s free, in a way where you don’t have somebody saying, ‘What are all those black kids doing in the corner of the lunchroom by themselves?’ It’s very different.”

Tell Them We Are Rising illustrates just how critical these spaces are for community and progress. And though Mr. Nelson didn’t graduate from an HBCU, for him the Vineyard offers a similar environment, one he chronicled in his previous film A Place of Our Own.

“Martha’s Vineyard has been kind of like an HBCU, because it’s been so nurturing for me. You know these are people who knew me, I grew up with a community here.”

The Martha’s Vineyard Film Center will screen Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities on Thursday, August 17 at 7 p.m. at the Strand Theatre. A Q&A with director Stanley Nelson will follow.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »