A widely debated proposal to install synthetic playing fields at the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School continues to draw debate as it heads to the Martha’s Vineyard Commission for review later this month.

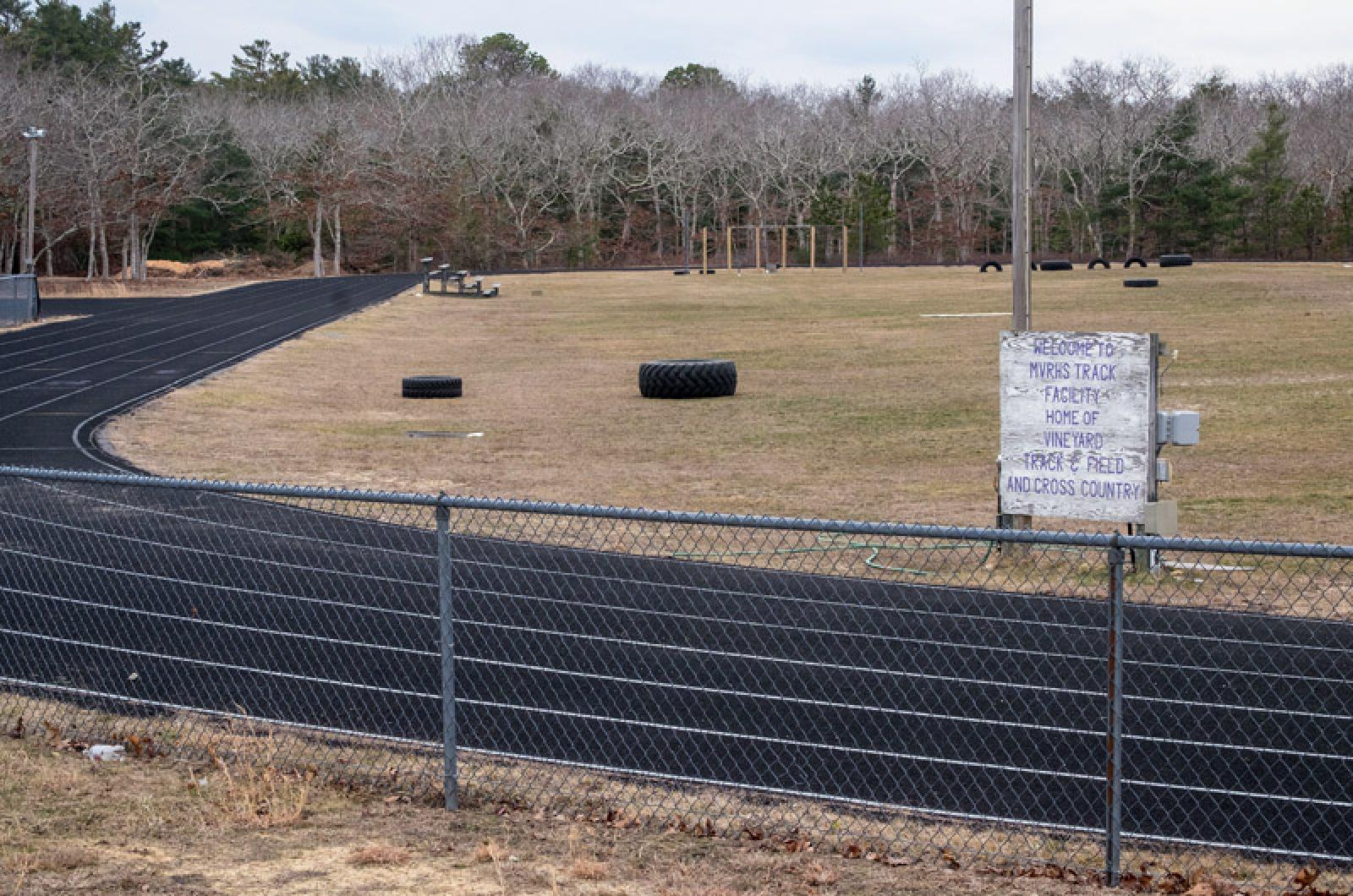

Many have welcomed the proposal as a cost-saving measure, in light of the high school’s aging athletic fields, one of which is so worn and compacted that it can no longer be used for competitions. But others continue to advocate for more natural solutions.

The community group MV@Play hopes to begin a three-phase project to convert the high school playing fields into a modern athletic complex, beginning with a new track and synthetic field this year. But as it gears up for the MVC review, some Islanders are eager to see a formal cost analysis of the alternatives, which so far has not been done.

The commission land use planning committee will hold a preliminary meeting Feb. 13, in part to determine what materials are needed prior to a public hearing. The commission has already received dozens of documents, including letters for and against the proposal, which are posted on its website.

High on the list of questions to be answered is the long-term cost of artificial turf versus natural fields.

“As it stands there are still very gray areas as to what the different costs associated with their project would be,” high school committee member Robert Lionette told the Gazette this week. “We have no sense of what it would cost us to not only maintain the grass fields — but which fields, what upgrades need to be done in the irrigation systems, what fields need to be completely regraded, and what ones just need a little more TLC. We can go out there and have a good guess, but a systematic analysis of this hasn’t been done.”

When it began working with the high school more than a year ago, MV@Play presented a general comparison of synthetic and natural surfaces, showing that on a one-to-one basis, a synthetic field would cost about $200,000 more than a natural field over 13 years. But organizers also said more than twice as many natural fields would be needed to handle the school’s 2,338 events per year, implying a savings of about $480,000 over the lifespan of the product.

Mr. Lionette has called for the high school to conduct a needs analysis, acknowledging that the commission’s review comes first. The timing of the MV@Play offer has extra appeal, coming as it does when the school has so many potentially expensive infrastructure needs, he added.

MV@Play plans to finance the project through donations, although most of the money raised so far has been used to

prepare for the MVC review, founding member David Wallis said this week. He said it was too soon to estimate the overall cost for the project, although phase one was earlier estimated at about $3.5 million.

The group has yet to choose a contractor, although it has been discussing the project with R.A.D. Sports of Rockland, and has a potential manufacturer in mind, Mr. Wallis said. Gale Associates of Weymouth, which is designing the project, plans to put the project out to bid on behalf of MV@Play following the MVC review, according to statements by the company. Under the term’s of MV@Play’s licensing agreement with the high school, the project is allowed to circumvent the public bidding process.

It is difficult to get a clear picture of the actual costs of synthetic versus natural turf because of the many factors involved.

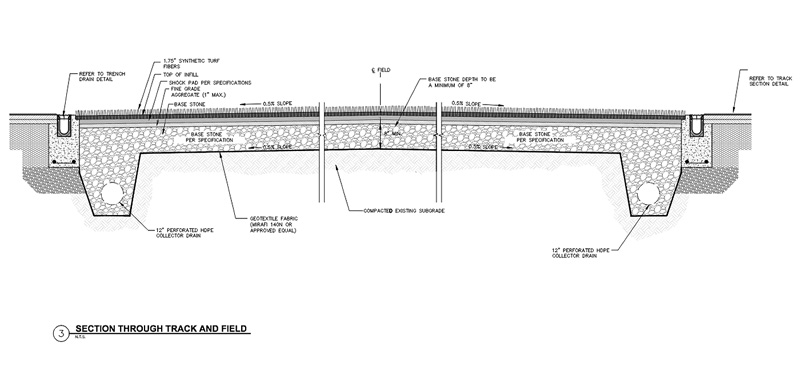

John Chaffin, a regional sales manager for R.A.D., provided a general cost analysis by manufacturer Shaw Industries, which places the initial cost of installation at around $680,000, compared to $450,000 for a natural field.

Installation costs depend on the size of a field, the type of surface and other factors. In addition, synthetic fields typically need to be replaced every 10 years or so, which Mr. Chaffin said would be about 60 per cent of the cost of installation.

Proponents of artificial turf often point to the potential for revenue as an offset to the cost.

Public concerns surrounding the safety of crumb-rubber, the infill most commonly used in synthetic fields, led MV@Play to pursue an alternative material made from cork, coconut husks and silica. Mr. Chaffin said his company has installed at least 20 of those fields around New England, and that one benefit is a lower surface temperature

than crumb rubber. But he added that the organic material may also require irrigation, adding to the cost of maintenance. According to a Gale Associates summary of infill options prepared in 2015, the alternative material could add $325,000 to overall costs.

Proponents often point to lower maintenance costs over time, but those numbers vary widely. One company, FieldTurf, estimates annual maintenance costs at about $5,000, compared to about $52,000 for natural grass. Shaw puts the figures at about $2,000 and $58,500, respectively. However, those numbers do not include the cost of replacement, which Mr. Chaffin said presents too distant a target for an accurate estimate.

The Massachusetts Toxics Use Reduction Institute (TURI), a research arm of the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, conducted its own analysis last year, drawing from news articles, the turf industry and conversations with facilities managers. It found long-term savings related to natural turf. As one example cited in the report, the Sports Turf Managers Association has estimated between $197,000 and $753,000 in total costs over 16 years for natural grass, and between $1.19 million and $1.68 million for synthetic turf.

“In nearly all scenarios, the full life-cycle cost of natural turf is lower than the life-cycle cost of a synthetic turf field for an equivalent area,” the TURI report concludes.

It’s unclear how long a synthetic field would last at the Island high school, although Shaw typically offers an eight-year warranty with its fields. Mr. Chaffin said the life of a synthetic field depends mostly on the amount of sunshine, and the amount of play, both of which will eventually break down the fibers. But with relatively moderate use compared to some venues, and a temperate New England climate, he didn’t believe those factors would be a problem on the Vineyard.

He said natural grass fields are only good for two or three events per week, after which they too will begin to break down. “That’s when they become dangerous,” he said, adding that he counts injuries as one indirect cost of grass fields.

Mr. Wallis said MV@Play does not currently include the cost of replacement in its estimates, although the group hopes to establish an endowment to cover longer-term costs, including replacement.

Some residents are uneasy about the idea of unaccounted future costs. Rebekah Thomson of the advocacy group Vineyarders for Grass Fields has pressed the MVC to collect more material prior to its review, including information related to long-term maintenance and labor. In a recent letter to the commission, she notes that a licensing agreement with the high school does not hold MV@Play accountable for future costs.

“We have been pressing for a long time,” Ms. Thomson told the Gazette this week. “Clearly from the information [the high school] has submitted, I don’t think anyone is asking this question.”

John Wilson, a lacrosse coach at the high school, said grass fields would be an ideal solution, but it is challenging to maintain natural turf during a busy athletic season.

“I don’t think you are going to find anybody who does not believe that we should have really nice grass fields,” said Mr. Wilson, who is also a former regional sales manager for Turf USA. “But given the amount of use these fields get, and the vagaries of the weather around here, I don’t think that can serve the goal.”

A key selling point for synthetic turf is its ability to support more frequent use, in part because it does not need time to rest. Companies often frame the value of their product in terms of cost per hours of use, which bolsters the argument against natural grass.

As for revenue, Mr. Wallis envisioned some income from the athletic complex at the high school — including from club teams and youth groups, although he said a user fee was still conceptual.

High school superintendent Matthew D’Andrea was unavailable for an interview this week, but said in an email that he was unaware of any groups currently being charged to use the fields. “However, user fees would be looked at as a way to generate revenue for an artificial turf replacement plan,” the superintendent said.

Ms. Thomson didn’t find much comfort in the idea of a user fee, which she worried might disadvantage low-income families with kids in youth sports leagues.

“Will people who want to use the track have to show insurance? I can’t imagine how that would be implemented, and they certainly don’t explain it,” she added.

Meanwhile, Mr. Wallis said it was too soon to say how the community might use the new fields, although the goal is to create an Islandwide resource. Over the last year, he said, he has spoken directly with other schools and organizations in the region, all of which are happy with their synthetic fields. Mr. Wilson reported similar conversations throughout his many years in sports. “I have not run into anybody at a school that’s not been happy with what they’ve put in,” he said.

But he also acknowledged the value of having clear alternatives.

“If we are going to do something, people need to be able to make a reasonably informed decision as to what’s best,” he said. “Right now there is nothing to compare synthetic fields to, other than what we already have, and that’s not very good.”

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »