A landmark energy bill that passed in the final hours of the legislative session on Sunday opens the door to offshore wind energy developers, but prevents the embattled Cape Wind project in Nantucket Sound from competing for state-required energy contracts.

The bill requires utility companies in the state to buy up to 1,600 megawatts of offshore wind energy over the next 10 years, making it the largest commitment of its kind in the country. The companies must also purchase up to 1,200 megawatts of hydropower or other renewable energy.

Four developers have planted their flags in federal waters around Vineyard, including a partnership between OffshoreMW and Vineyard Power, the Island energy cooperative. But the bill limits the new contracts to companies whose projects are at least 10 miles from shore and who acquired federal leases in a competitive process after Jan. 1, 2012. That excludes Cape Wind, which pioneered the U.S. offshore wind market beginning around 2001 with its plan for turbines on Horseshoe Shoal, an area of federal water in Nantucket Sound surrounded by state waters. Cape Wind never got off the ground and has been sidelined by lawsuits over the years.

Cape Wind president Jim Gordon said this week that he plans to press forward despite the recent setback. “Our company will evaluate our options for Cape Wind and continue our ongoing efforts of implementing a variety of clean energy solutions,” he said in a written statement.

But the path forward is unclear. Early last year, Eversource Energy and National Grid (the only regulated utilities in the state) severed contracts with Cape Wind after the company missed a key financing deadline. The company fought the decisions, claiming “force majeure,” or an act of God, in light of relentless litigation. (Cape Wind lists 32 court cases filed by opponents of the wind farm as of 2014, with 26 rulings in favor of the company and five cases withdrawn.)

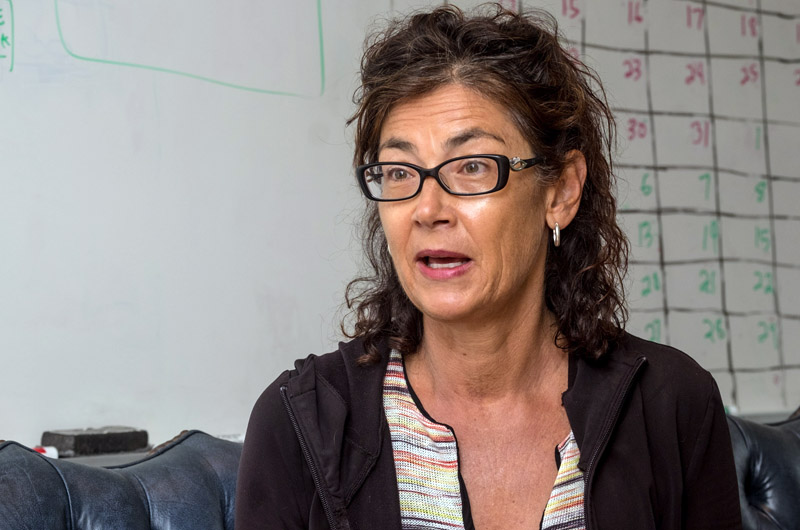

“The public perception is that the development is dead,” said Audra Parker, president of the Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound, a nonprofit based in Hyannis that has worked tirelessly to scuttle the project through lawsuits and public campaigns. “But the developer continues to be as persistent and tenacious, I suppose, as we are.”

The new energy bill could have restored the much-needed contracts, since it requires a competitive bidding process. A seven-member Cape delegation, including outgoing Cape and Islands Rep. Timothy Madden, had pressed for the language excluding Cape Wind from the bill.

The legal battles have continued this year. Most recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals overturned two district court decisions related to a 2010 lawsuit that involved the Alliance, Wampanoag Tribe and other groups. As a result, Cape Wind must revise its environmental impact statement and its proposal for mitigating the effect on piping plovers and roseate terns in the lease area.

Both Cape Wind and the Alliance claimed victory in the decision, which stopped short of vacating Cape Wind’s lease and allowed most of the earlier decisions to stand. But the list of setbacks is growing. In April, the state Energy Facilities Siting Board chose not to extend a permit for future transmission lines to bring the energy ashore (Cape Wind has appealed), and a Federal Aviation Administration permit is listed as having expired last year.

Mr. Gordon highlighted the company’s role in “validating the benefits of offshore wind for the commonwealth,” and framed the conflict surrounding Cape Wind as a case of nimbyism. “The influence of fossil fuel billionaire Bill Koch and other wealthy NIMBYs and the decision by the legislature and Baker administration to exclude a bonafide competitor with the most advanced, developed offshore wind project unfairly undermines a true competitive process,” he said in the statement.

Other offshore wind developers this week hailed the energy bill as an invitation to press forward with their projects. Vineyard Power president Richard Andre pointed to the importance of utility contracts in making offshore wind a reality. “Without this we’d almost be moving toward 100 per cent natural gas,” Mr. Andre said, adding that without the state mandate, “there would be no offshore wind farms.”

Along those lines, Vineyard Power has drafted its own legislation, known as an act for community empowerment, which would allow municipalities to enter into long-term renewable energy contracts on behalf of their citizens. Mr. Andre said the law would help stabilize prices over time and allow towns to buy more renewable energy than the state requires. The proposal was part of the Senate version of the energy bill, but didn’t make it into the more streamlined House version. “We’re going to build on that and go to the next session,” Mr. Andre said.

Vineyard Power and OffshoreMW have leased 166,886 acres beginning about 14 miles south of the Island, just east of another area leased by Dong energy, the world’s largest offshore wind developer. The two projects have attracted far less criticism than Cape Wind, which would have been easily visible from the Vineyard and the mainland and lacked the public review now required for identifying offshore wind areas. Both companies have begun reaching out to the local community as they begin to move from planning to implementation.

Deepwater Wind, which is developing a site off Rhode Island, is also expected to bid on the new energy contracts.

“Now these developers have confidence to develop the sites,” Mr. Andre said, “because they know that there will be a customer at the end.”

Thomas Brostrom, general manager of Dong Energy in North America, praised the bill as a victory for the state’s residents and businesses. “This bill will allow the creation of a viable offshore wind energy industry here in Massachusetts, delivering cost effective clean energy, helping the state reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” he said in a press release. He expected the company’s wind farm to power up to half a million homes in the state and create about 1,000 jobs during construction.

Both Vineyard Power and Dong Energy hope to begin surveying the sea floor in their lease areas this year. Dong representatives met some resistance among the Island’s commercial fishing fleet this winter, but have insisted on coming up with a compromise. Mr. Andre said the surveys in his area would begin in September.

In another step forward, Dong Energy filed an application with ISO New England on Monday to connect 800 megawatts of energy to the regional grid. In a separate statement, Dong Energy noted the planned closure of the Brayton Point Power Station in Somerset next year, which would free up about 1,000 megawatts of interconnection capability. Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station in Plymouth is slated to close in 2019, further underscoring the state’s interest in renewable energy. (The new energy bill sets up a citizens advisory panel related to the decommissioning of the station.)

The bill also promotes the use of energy storage technology, and requires that the state develop a plan to repair gas leaks, among other provisions.

The Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound has yet to endorse any offshore wind project, although Ms. Parker said the group supports the public process for selecting the sites south of the Island. “I think there is a recognition that we don’t have to start with Cape Wind, that you can start with these other projects,” she said. “There is just that whole notion of ‘let’s do it right, and let’s stop fighting over this one project.’”

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »