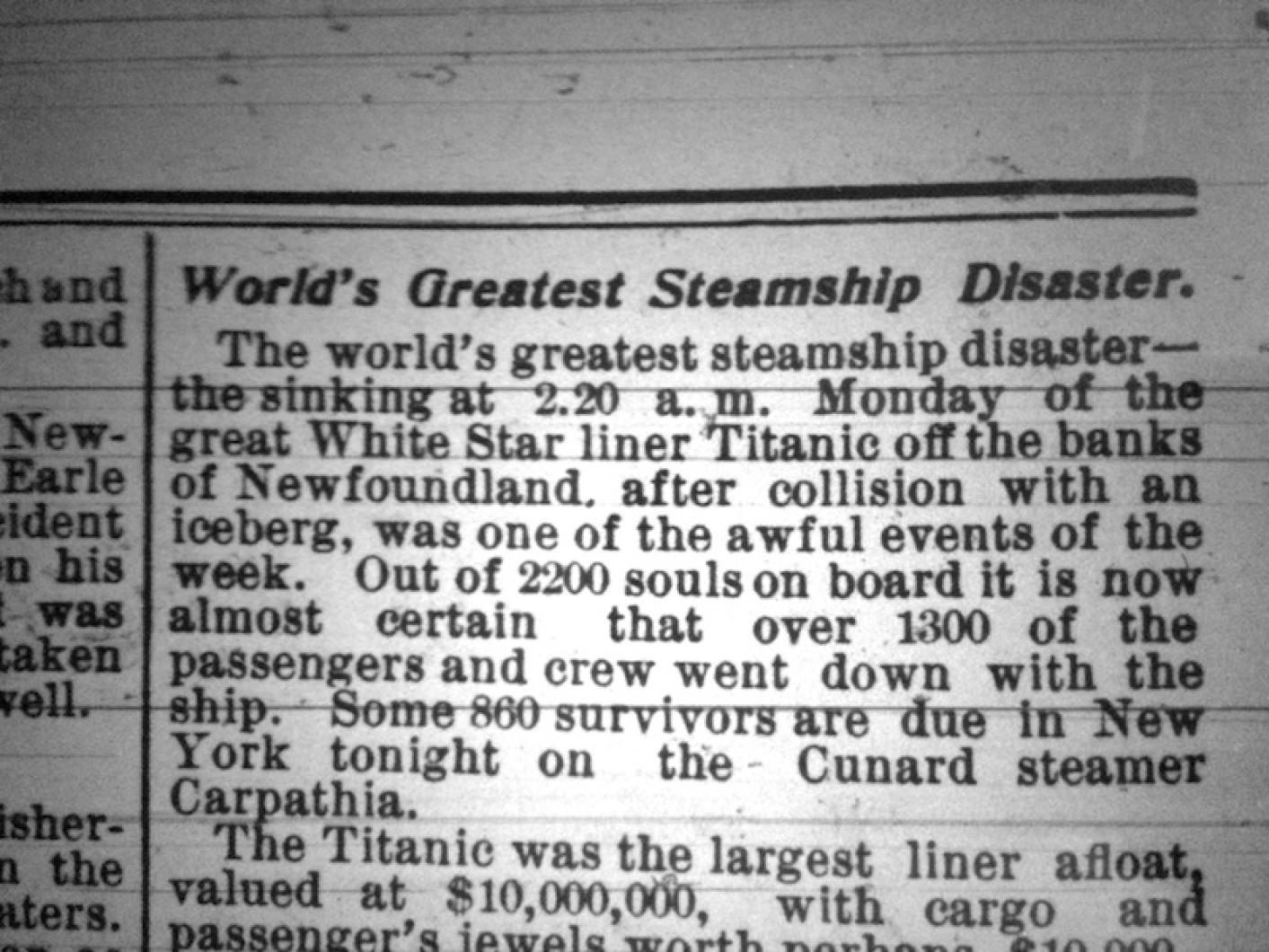

From the April 1912 editions of the Vineyard Gazette:

The world’s greatest steamship disaster — the sinking at 2:20 a.m. Monday of the great White Star liner Titanic off the banks of Newfoundland, after collision with an iceberg, was one of the awful events of the week. Out of 2,200 souls on board it is now almost certain that over 1,300 of the passengers and crew went down with the ship. Some 860 survivors are due in New York tonight on the Cunard steamer Carpathia.

The Titanic was the Largest Liner afloat, valued at $10,000,000 or more. Her crew numbered 860 persons. It is estimated that the wealth of the passengers in her first cabin represented an aggregate of $500,000,000, many of these wealthy men being among those supposed to have been lost, prominent among whom is Col. John Jacob Astor of New York, the head of the famous family of that name.

The Titanic herself lies buried two miles beneath the ocean’s surface, midway between Sable Island and Cape Race. Her position when she struck the iceberg was given as latitude 41.46 N., longitude 5-.14 W. According to the Carpathia’s advices the liner, which struck the iceberg at 10:25 o’clock Sunday night, sank at 2:20 o’clock Monday morning, nearly four hours later, in latitude 41.46, longitude 50.14. The Titanic was 882 ft. 9 in. over all, extreme breadth of 92 ft. 6 in. and when loaded drew 34 feet of water. She had a displacement of 66,000 tons, with a gross tonnage of 45,000. The total height from keel to navigation bridge was 104 feet.

That Capt. Smith believed the Titanic and the Olympic to be unsinkable is recalled by a man who had a conversation with the veteran commander on a recent voyage of the Olympic.

The talk was concerning the accident in which the British warship Hawke rammed the Olympic.

“The commander of the Hawke was entirely to blame,” commented a young officer who was in the group. “He was showing off his warship before a throng of passengers and made a miscalculation.”

Capt. Smith smiled enigmatically at the theory advanced by his subordinate, but made no comment as to his view on the matter.

“Anyhow,” declared Capt. Smith, “the Olympic is unsinkable, and the Titanic will be the same when she is put in commission.

“Why,” he continued, “either of these vessels could be cut in halves and each half would remain afloat indefinitely. The non-sinkable vessel has been reached in these two wonderful craft.

“I venture to add,” concluded Capt. Smith, “that even if the engines and boilers of these vessels were to fall through their bottoms the vessels would remain afloat.”

Major Arthur Peuchen of the Queen’s Rifles of Toronto, Canada, one of the survivors of the Titanic disaster, is credited with this statement to a New York paper:

“Less mother of pearl in the cabin and a searchlight on the bow would have saved hundreds of lives and the Titanic,” he said just before leaving for his home last night.

“Like other passengers on the Titanic, I was amazed that there was either no searchlight at all or at least none in use. Had there been, that iceberg would have been detected. The ship would have been saved and practically all the passengers.”

It is difficult to choose between a hundred stories of heroism, but the people who knew and loved Henry B. Harris will like to recall his last words to his wife: “Don’t worry, Renee, sweetheart, I’ll get the next boat, and you know I’m a good swimmer.” This was said with more of a laugh than a smile. It comforted and reassured the woman, as it was meant to do; but Mr. Harris was under no illusion, and, when he had persuaded her to safety, he turned to a fellow passenger and observed, “Nothing for us, eh, but to die like gentlemen?” Yet that was easy. It was the spirit in which a man who was never “theatrical” outside of his playhouses had always lived.

There were endless incidents upon which this catastrophe, which ranks as one of the great sea tragedies of the ages, may be profitably discussed. It is worth while, as many are doing, to point out the folly of placing life upon a cast by taking the northern course across the Atlantic in a treacherous season.

We might, and we do, pay tribute to the captain, his officers, and men of high and low degree, sailers of the Anglo-saxon race who care for the souls of the seagoers in the spirit of McAndrew:

“Maybe they steam from grace to

wrath

to sin by folly led,

It isna mine to judge their path -

their lives are on my head.”

These men were true to the lesson it is theirs to learn of “Duty and restraint, obedience, discipline.” Many of them gave the last full measure of their devotion while the few who were saved begin life over again.

Compiled by Hilary Wall

library@mvgazette.com

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »