Portly, slow and trashy are only complimentary to a spider crab.

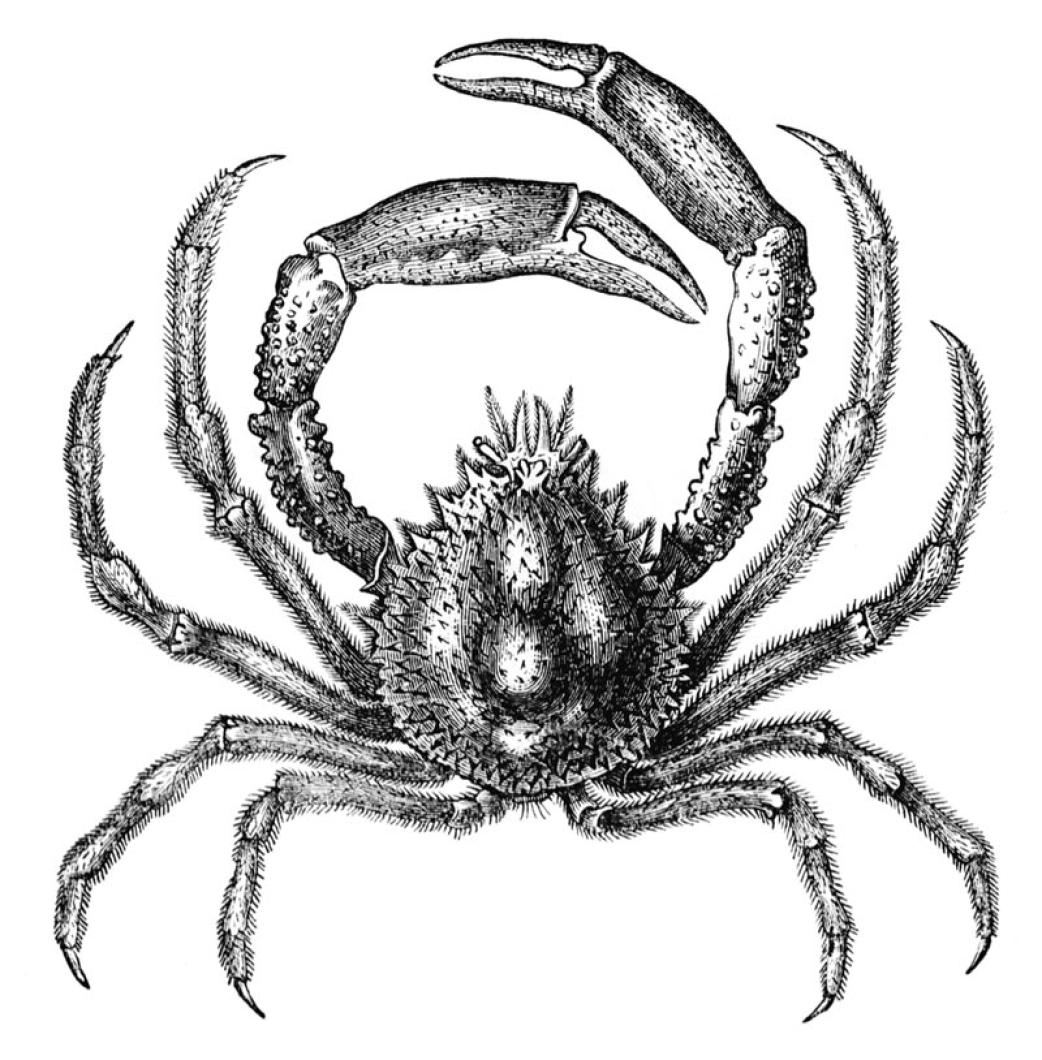

Spider crabs, also called portly crabs, need little introduction. Who wouldn’t recognize these distinctive denizens of the depths? That is, of course, if you can see them. Camouflage is their specialty. This crustacean’s shell is brownish like its surroundings, and round like rocks in the sea. It is easy to miss as it lumbers along because its shell is covered with spines and tubercles that make it blend well into the underwater habitat. This trick is accomplished by small hooks on the shell (or carapace) that act like Velcro, holding on to algae, small invertebrates and detritus.

This backpack of goodies serves another purpose besides concealment. It actually provides young crabs with a “grab and go” meal selection. Smaller spider crabs intentionally place these morsels on their shell and will reach back for a snack! With all of those peculiar pickings on their shell, it is no wonder that they are also called decorator crabs.

Lately, there has been a crowd of these crabs in our ponds. Especially in Sengekontacket, where I spend much of my time, spider crabs are clamoring and clustering in larger numbers than I have seen in some years. Although nature is full of mysteries, there are some observational and behavioral clues that might explain spider crab health and prevalence in the pond.

All animals are affected by competition. One spider crab rival is the green crab. This invasive species came in ballast water more than 150 years ago, and has outcompeted (and eaten) native species and their prey, reducing the native’s numbers and food supply. While I have seen large numbers of spider crabs, green crab numbers seem to be down this season. Perhaps only a temporary win for the natives, but a good thing, nevertheless.

Another factor that might explain spider crab gatherings has to do with pond conditions. Spider crabs are stenohaline animals, meaning that they can’t handle salt fluctuations in their watery environs. Thus, having a steady salinity, as we do in Sengekontacket Pond, allows for successful spider crab survival.

A final observation comes from recent research on these crabs. Studies show that spider crabs aggregate when they are molting, forming large pods, whose gathering likely provides protection for individuals and the group alike. We all know that there is strength in numbers.

Unlike other crabs, spider crabs prefer to walk straight. Aristophanes, who claimed that “You can’t teach a crab to walk straight,” must not have met the straight-walking spider crab. Look to these legs to distinguish the gender of the gentle spider crabs. Males are larger than females in body size and have larger walking legs than their female counterparts. The legs and pincers are two times bigger than the female’s, and pincers can be over six inches long in a very sizeable crab.

With poor eyesight, spider crabs lethargically lumber along. They compensate with sensitive tasting and sensory organs at the end of each walking leg. Clearly these traits have suited the spider crab, which is a living fossil, having been around unchanged for hundreds of millions of years.

With their endearing qualities and knack for survival, it is no wonder that T.S. Eliot suggested that he, too, “should have been a pair of ragged claws, Scuttling across the floors of the silent seas.”

Suzan Bellincampi is director of the Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary in Edgartown.

Comments

Comment policy »