Some people regard social networks (like Facebook) as a waste of precious time. Others find them a lifeline to a meaningful social world. I’m in the latter category, especially on an Island like Martha’s Vineyard. How come? To explain, I’m going to take a little detour in this conversation — so please stay with me.

Datebook: March, 1983, mid Pacific en route from Guam to Satawal, a tiny island in the Carolines, to make a documentary film. Every night on the voyage, our captain tunes his ham radio to Alice’s net where sailing vessels from all over the Pacific are connected to each other by bouncing radio waves off the ionosphere. Their voices are ghostly, accompanied by whistles and wheezes, but we listen intently.

Here’s Nina and Jed on their Freedom Forty cruising from Pohnpei to Chuuk. They’re having engine problems — which is not serious in mid-ocean but will be when they make land and, even more importantly, the engine powers their desalinator so without it they may run out of fresh water.

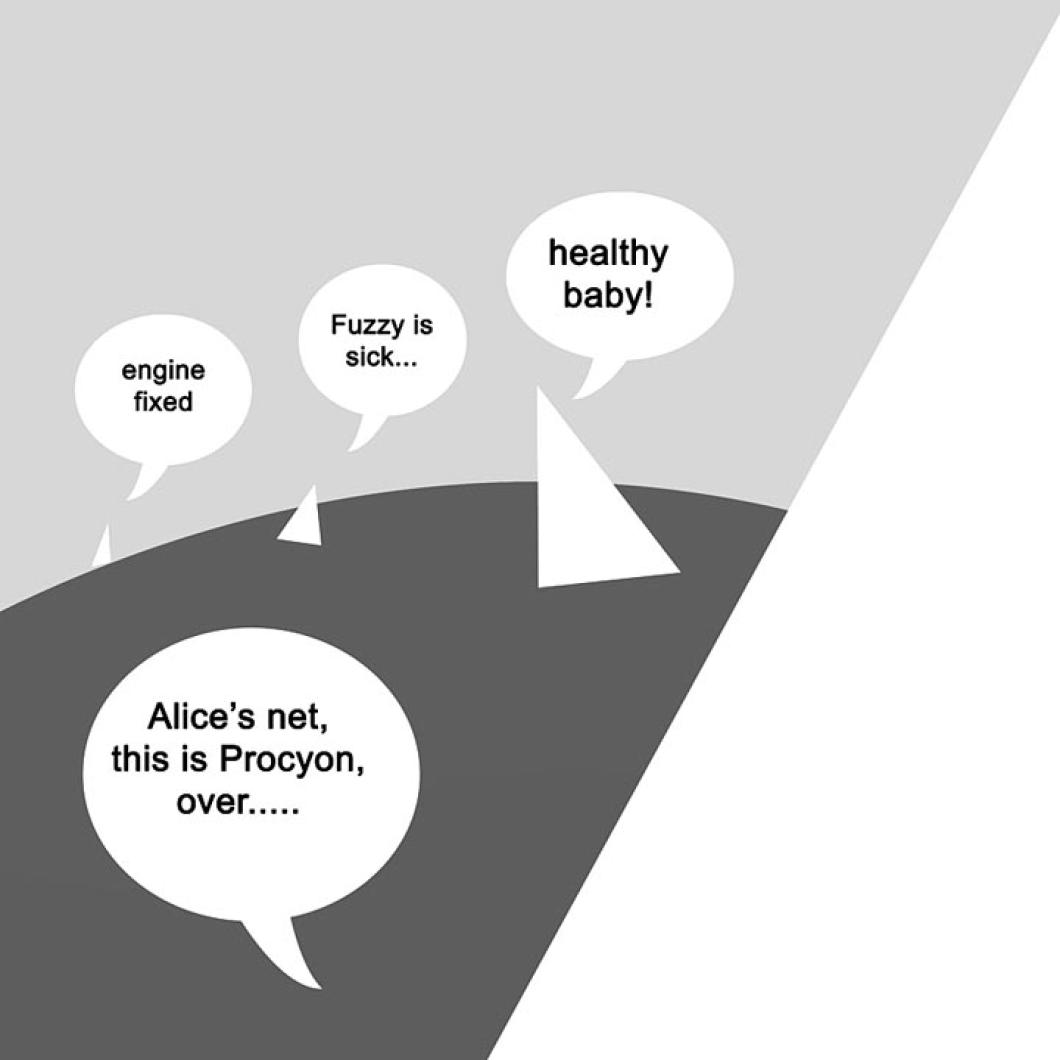

“Alice’s net, this is Nina. Jed has been in the bilge for hours and we may have found the problem. So far, the diesel is running fine. A little blue smoke — but we’ve powered up the desalinator and think the problem is solved.”

Methodically, other yachts call in and give their position and status for the day. A Far Cry is en route from Majuro to Chuuk having made 100 miles in 18 hours in the trades. All well. Moana is anchored somewhere — there’s too much static to tell where. Procyon needs help making contact with a ham operator who can relay messages from San Diego, where a baby is expected in their family. Our captain helps with the relay and we wait.

Meanwhile the calls continue. There’s a low pressure area north of us that needs watching. The diesel fuel at the main pier in Chuuk may be contaminated with water. Sam and Martha, aboard Dingbat, report that Fuzzy, their cat, is sick.

“Do you know these people?” I ask the captain.

“Not many personally,” he says, “but even so I feel I know them intimately by following their little problems every day on the net. We may never see each other, but often we will — in some port. If I’m going to Tahiti, I already know who will be there and I’m sure to row over and say hi, giving my call sign, and I will be invited aboard for a gam (sailor’s talk for a conversation).”

Procyon checks in, the baby was delivered and all are fine.

It’s a little like that on the Web. The Pacific is a very big ocean, maybe ten million square miles, but it’s a bounded space nevertheless. Martha’s Vineyard is much smaller, of course, but bounded also. When I “meet” someone on Facebook I know I will heave into some port of call ( a party, the P.A. club, a restaurant) and encounter them personally.

The Web, like the more primitive ham radio net, connects us voyagers to each other. We listen in, or in the case of Facebook — we read the posts — and we get to know each other. So I’m certain that when I row into some Island gathering I will encounter a few Facebook friends and we’ll sit down and exchange intimacies in a way we could not have without the Internet. Like the sailors who talk to each other on Alice’s net — we’re all voyagers. Anything that makes it easier to connect is a good thing.

Comments

Comment policy »