Mill Pond, the placid 17th century swan-dotted pond that graces the entrance to the village of West Tisbury, is the scene of a quietly growing conundrum in this rural town. Amid fears that the manmade pond — which averages a depth of a foot and a half — will soon fill in, West Tisbury is considering a variety of engineering options to retain its aesthetic appeal far into the future, while possibly improving the pond’s limited ecological function. But some see the effort to save the pond as misguided.

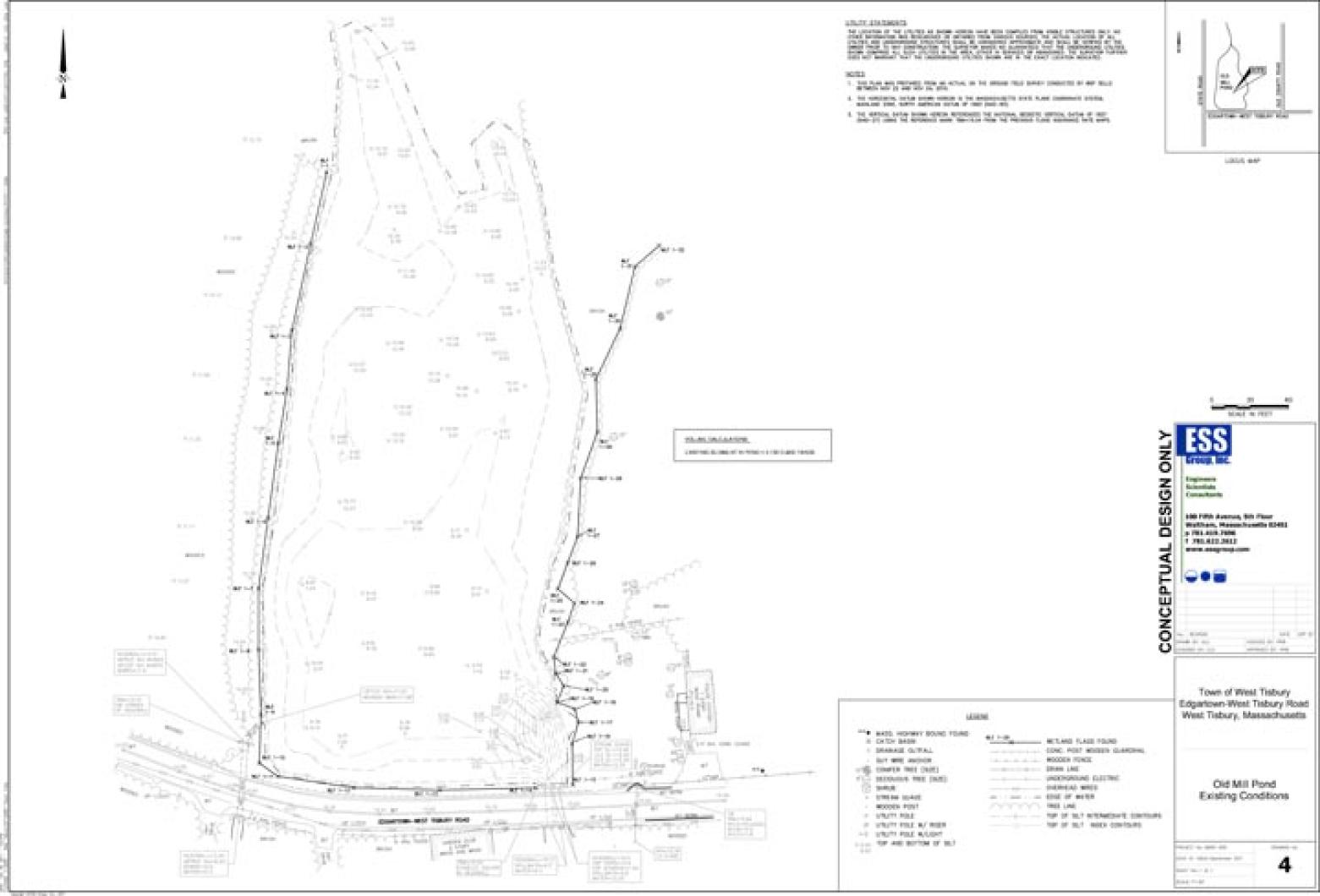

Built in the 1600s, the Mill Pond dam once provided hydropower to the grist and wool mills along its banks. It also created the pond, which periodically has been dredged through the centuries to provide rushing water to the mills. When the mills were shuttered, the dredging continued to preserve the pond. Dredged at least every 50 years (the last time was 1970), the pond is now at a crossroads as town planners balance its ecological and aesthetic value with financial considerations. A Mill Pond committee formed by the town commissioned the engineering firm ESS Group to study the pond, and the results were presented on Wednesday night at the Howes House.

Dredging has emerged as the only practical way to combat an ever-thickening layer of sediment, aquatic weed growth and algae in the shallow pond. Carl Nielsen of the ESS Group offered three options to the town. The first and least expensive option, at $150,000 to $200,000, calls for dredging only the foot-thick layer of organic sediment lining the pond’s bottom. The organic material feeds the rampant algae growth and provides a fertile substrate for weeds, which then trap even more sediment. The benefit of such a project would be almost entirely aesthetic (the pond would likely still be too shallow for overwintering fish), would require the installation of a geotextile liner on the pond’s bottom to keep the water from simply draining through the exposed sand, and would last for only 30 years.

Longer-term solutions require deeper dredging. The most striking — and heavily-engineered — option proposed by Mr. Nielsen would require cutting the Mill Pond in half. The front half of the pond would be dredged to a depth of eight feet, suitable for overwintering fish. In the back half, farther from the Edgartown-West Tisbury Road, engineers envision building a labyrinthine system of berms to create an artificial wetland that would sap nitrogen and phosphorus from the nutrient-loaded pond; this in turn would then benefit the Tisbury Great Pond farther downstream. Mr. Nielsen said the ecological benefits of the project would make it an attractive candidate for state funding. On Wednesday Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group director Rick Karney colorfully described the shape of the artificial wetland as “intestinal.”

“If that’s not the look you want, that wouldn’t be the solution for you,” replied Mr. Nielsen.

In his final alternative, Mr. Nielsen suggested removing 1,560 dump truck loads of material from the pond, effectively creating two deep sections. The back section would collect sediment that could be removed by the town from time to time. The solution would last 70 years and would cost between $450,000 and $700,000.

How fast the Mill Pond is filling in is also a matter of some contention and confusion, Mr. Nielsen admitted.

“It could be 20 years, it could be 30 years, it could be 50 years and it might never fill in entirely,” he said.

In the report, ESS Group states that the pond traps a net 18.7 cubic yards of new sediment every year. To Prudy Burt, a West Tisbury resident and member of the conservation commission who opposes dredging the pond, the number is not alarming.

“I don’t think anyone should take away from this report that we’re able to quantify that the Mill Pond will end any time soon.” she said. “Chicken Little can rest easy.”

While the Mill Pond is a vestige of colonial times, Ms. Burt favors a solution that is even more of a throwback. If the dam was removed altogether, as she advocates, the landscape would return to a vegetated wetland bisected by what would become the Mill Brook.

“When I see revetments built in and wetlands systems built in — well, we could just have a wetland system, it could be that easy,” she said.

Ms. Burt has contributed to the conversation about the Mill Pond before, arranging a talk in 2010 by Beth Lambert, river restoration program coordinator for the state Division of Ecological Restoration. Tomorrow, acting as a town citizen and not on behalf of the conservation commission, Ms. Burt has invited another river restoration advocate to speak at the West Tisbury Library at 3:30 p.m. Michael Hopper is president of the Sea Run Brook Trout Coalition.

In a telephone conversation with the Gazette yesterday, he said the benefits of dam removal are plainly obvious. In 2009 four dams were removed along the Red Brook which runs through Plymouth, Wareham and Bourne. The removal was largely funded by stream restoration grants from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which Mr. Hopper said would also be available to the Vineyard.

“The effect was really dramatic,” he said. “We saw a dramatic increase in brook trout and what’s more important, we saw a dramatic increase in sea run brook trout because they had been blocked from getting out into the marine environment for about 50 generations. We’re seeing a lot of species we haven’t seen around the stream in a long time.”

Removing the Mill Brook dam would benefit the system’s own unique suite of creatures, he said.

“Dam removal at Mill Pond would definitely improve passage for American eels and improve passage for blue-back herring,” Mr. Hopper said. “I think the real reason I would advocate for dam removal is you’re removing the cost of dredging the pond from the town permanently.”

But removing the dam would also remove one of West Tisbury’s signature landmarks and a link to its past. It could also affect the wider network of familiar ponds around West Tisbury (Maley’s Pond farther downstream is used as a water source for firefighting). Bob Woodruff of the town Mill Pond committee summarized the situation on Wednesday.

“This is a complex little pond we’ve got here,” he said.

The Mill Pond Study is posted on the Gazette Web site at mvgazette.com.

Comments

Comment policy »