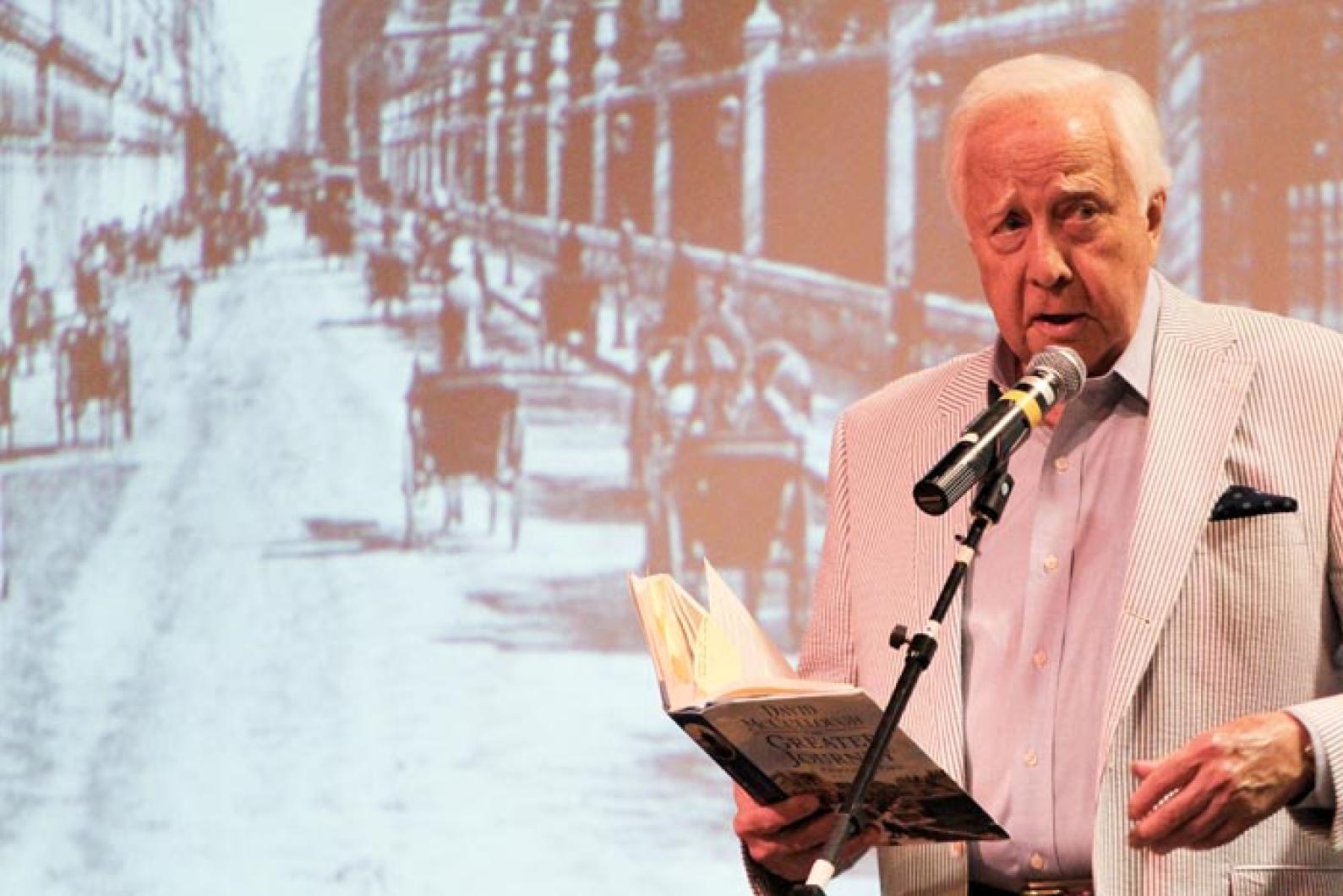

The West Tisbury Public Library is expanding, its patrons hope, to make room for more books like David McCullough’s The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. Mr. McCullough spoke at the Agricultural Hall on Wednesday to a rapt, full house, without notes and with his inimitable panache about the importance of libraries and the illuminating effect the City of Lights has had on its American visitors over the centuries.

West Tisbury learned last week that it would receive a $2.9 million state grant for its proposed $5 million renovation. But the library still must raise 25 per cent of the total cost of the project in private funds, and on Wednesday night Mr. McCullough did his best to rouse the philanthropic inclinations of those in attendance.

“Jefferson said any nation that expects to be ignorant and free expects what never was and never will be,” he said in a vigorous defense of libraries. “We are up against forces in the world that believe in enforced ignorance. We don’t, and this [library] system we have in every town in the country is one of our greatest thriving life-support systems.”

Mr. McCullough then launched into a meditation on the nature of historical events.

“Nothing ever had to happen the way it happened, it could have gone any way at almost any time,” he said. “Also, no one ever lived in the past. We talk about how they lived this way or that in the past. They never lived in the past. They lived in the present — it was their present not ours. Adams, Jefferson, George Washington, Franklin, they didn’t walk around saying, ‘Isn’t this fascinating living in the past? Aren’t we quaint in our funny clothes?’”

As he does in his books, Mr. McCullough then made that past present, offering a slate of anecdotes and insights into the experiences of Americans who shipped off for Paris between 1830 and 1920 armed not with a knowledge of French language or culture but only a desire for self-improvement.

Mr. McCullough highlighted what he called the “importance of moments of revelation” when that American enthusiasm and work ethic cross-pollinated with old world enlightenment ideals — whether it was Oliver Wendell Holmes, whose experience in a surgical theater dissolved his ingrained American aversion to cadavers and who imported the methods of a modern teaching hospital to his squeamish and woefully inexperienced peers, or Charles Sumner, who noted with some amazement the casual indifference of the French towards an integrated university classroom.

“Is it possible,” Mr. Sumner wrote in his journal in 1838, “that the way we treat black people in our country has to do with what we have been taught and is not a part of the natural order of things?”

“He had had a revelation,” said Mr. McCullough, “and as a consequence of that revelation in that year in Paris he came home to become the most powerful voice for abolition in the United States Congress.”

When Mary Cassatt first saw the pastel drawings of Edgar Degas in the window of a Parisian art store, she had a revelation. When James Fenimore Cooper first saw the Rouen Cathedral, he had a revelation. Samuel Morse, George E. A. Healey, Henry James and John Singer Sargent all left for Paris to raise their consciousness and all came back changed. And as a result they changed us, according to Mr. McCullough.

“These people didn’t want to get away from their country to prove that they were superior to their country,” he said. “They wanted to get the training and the competence and the confidence in their work to come back to raise the level of education, culture and American life.”

And the relationship went both ways. Standing before a striking, projected painting of the Statue of Liberty rising above the Parisian skyline Mr. McCullough called Lady Liberty “the biggest, most generous single gift from one nation to another ever in history.”

Mr. McCullough also said that he had never had a better time writing a book.

“Now many people think, sure, you had a great time because you got to go stay in Paris a lot,” he said. “Yes, we did go to Paris fairly often, but that was mainly to walk the walk and see how much I had gotten wrong.”

It was Mr. McCullough’s favorite book to write, he said, because of how much he learned. In his subjects he found an unquenchable thirst for knowledge and a tirelessness that humbled even the country’s most beloved historian.

“Their work was their life and they did not accept — as so many of us, alas, seem to do because of so much of the ballyhoo we’re subjected to — that ease and happiness are synonymous,” he said. “It was quite the reverse. To them hard work and happiness were synonymous.”

For inquiries about an upcoming patrons’ dinner with Mr. McCullough in a private home, please call Carol Brush at 508-693-3489.

Comments

Comment policy »