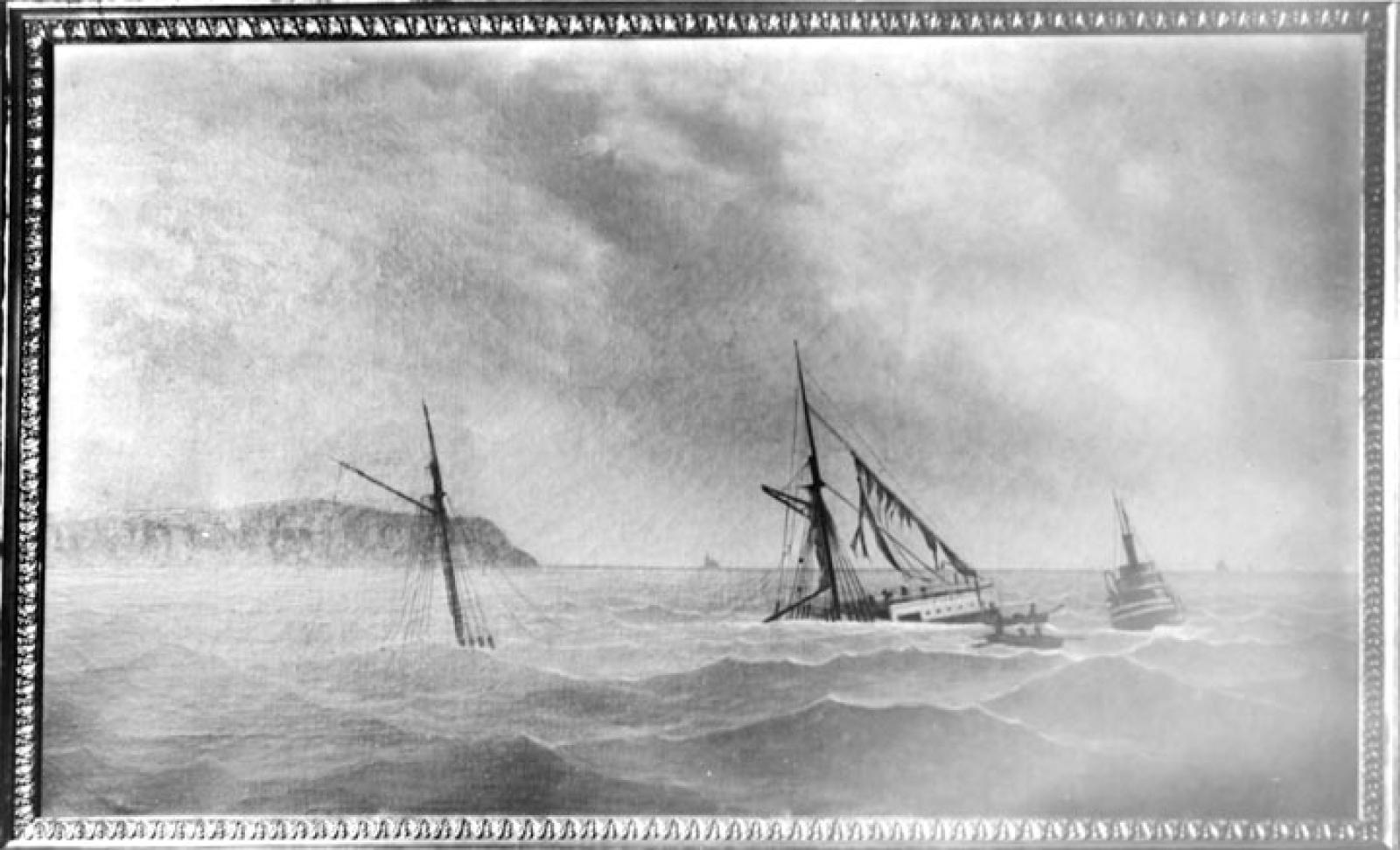

Jan. 18 marked the 127th anniversary of one of the worst marine disasters in southeastern Massachusetts, when the 275-foot steamer City of Columbus foundered on the rocks of Devil’s Bridge and sank a half mile off Gay Head. A total of 103 passengers and crew were lost.

But some 23 people were rescued from the icy sea in gale conditions by a small, hardy band of Islanders on that bitterly cold January night. Many were members of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head; others were Chilmarkers. All went out in surfboats to make the rescue in unimaginably rough conditions. Twelve of the rescuers later received awards from the Massachusetts Humane Society. Now an effort is underway to have the U.S. Coast Guard posthumously recognize the Islanders for their bravery.

“I first heard about it [the wreck of the City of Columbus] two years ago. I was researching nautical history of the Island,” said Lawrence N. Clark, a boatswain mate, first class with the Coast Guard who is involved in the effort to recognize the rescuers. Mr. Clark lives in South Carolina; his sister lives on the Vineyard and he has spent many summers on the Island.

Mr. Clark did some research on his own and later with members of the tribe, piecing together facts about what happened that night. In an appeal to the Coast Guard, former Cong. Bill Delahunt and Sen. John Kerry, he wrote:

“Although the 12 rescuers have received awards, I feel that they are deserving of Life Saving Medals from the Coast Guard for the following reasons: Six of the twelve men who made rescues did so while under the on-scene command of a United States revenue cutter (the revenue cutter Dexter).

“The twelve rescuers put themselves in harm’s way with rough sea conditions due to a gale and air temperatures below twenty-two degrees. It is also notable that the first crew of six Wampanoag Indians did not even have cork life vests on. In their haste of getting to the boat, the rescuers had forgotten to take life jackets.

“Had the Wampanoag rescuers perished, it would have been a huge economical blow to the village. These were their finest men and made their living fishing and whaling and without them supporting their families, the mere existence of the tribe would be threatened.”

Cheryl Andrews-Maltais, chairman of the Wampanaog Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) is a descendant of one of the rescuers, Samuel Haskins, one of the crew of the first surfboats to make it to the side of the wrecked ship. He was the son of Capt. Amos Haskins, a Gay Head whaleman.

Mrs. Andrews-Maltais and Bettina Washington, the tribe’s historic preservation officer, have researched the rescue for years on their own and are still collecting details about those who participated in the rescue. They welcomed the help from Mr. Clark.

The list of known rescuers follows.

In the first boat were Joseph Peters, who led the crew as boat steerer, Samuel Haskins, Samuel Anthony, James Cooper, Moses Cooper and John P. Vanderhoop.

On the second boat were James Mosher of Chilmark, in command, Leonard Vanderhoop, Thomas Jeffers, Patrick L. Devine, Charles Grimes, and Peter Johnson.

A third boat included a crew of Chilmarkers, Edy Flanders, Benjamin Mayhew, Edward Elliott Mayhew, Cyrus Look, Seth Walker and William Mayhew.

A fourth group of Gay Headers who were unable to make it through the breakers that night were Henry Jeffers, Raymond Madison, Thomas Manning, Simon Devine, John Anthony and Charles Stevens.

Ms. Washington said her great-great-grandfather was Thomas Manning, who participated in the fourth attempt. “I can recall these stories being told when I was young. It is part of our oral history. We didn’t read it in a book; we were told the story,” she said. “I cannot imagine now . . . . I cannot imagine suiting up and getting ready to go out in the rough seas, in the bitter cold and try and save somebody,” she said.

Yesterday, Jeff Hall, a spokesman for the Coast Guard District One, said the matter is before the district awards board which meets in Boston. No decision has been made yet on whether to grant the awards.

Ms. Washington hopes the decision is affirmative.

“This is a real source of pride among the Gay Head and Aquinnah people, whether they were able to save lives or made an attempt to reach the ship,” she said.

Comments

Comment policy »