Connor Gifford, a 28-year-old man from Nantucket, was born with some extra chromosomes. Sometimes that little bit extra can be a burden; other times, a boon. But it will always mean that Mr. Gifford has Down syndrome.

Roughly one out of 1,000 people are born with Down syndrome. They share specific and easily-recognizable aspects of appearance and behavior, similarities in facial features, body type and difficulties with speech and cognition.

However, there are other typical manifestations of the syndrome that are less easy to spot from across the street, but no less common. Many people with Down’s possess a unique candor, an innate kindness, sensitivity, openness and overall simplicity of vision and living that a neurologist might easily attribute to abnormal brain function, but which a friend, family member or coworker might regard as an asset.

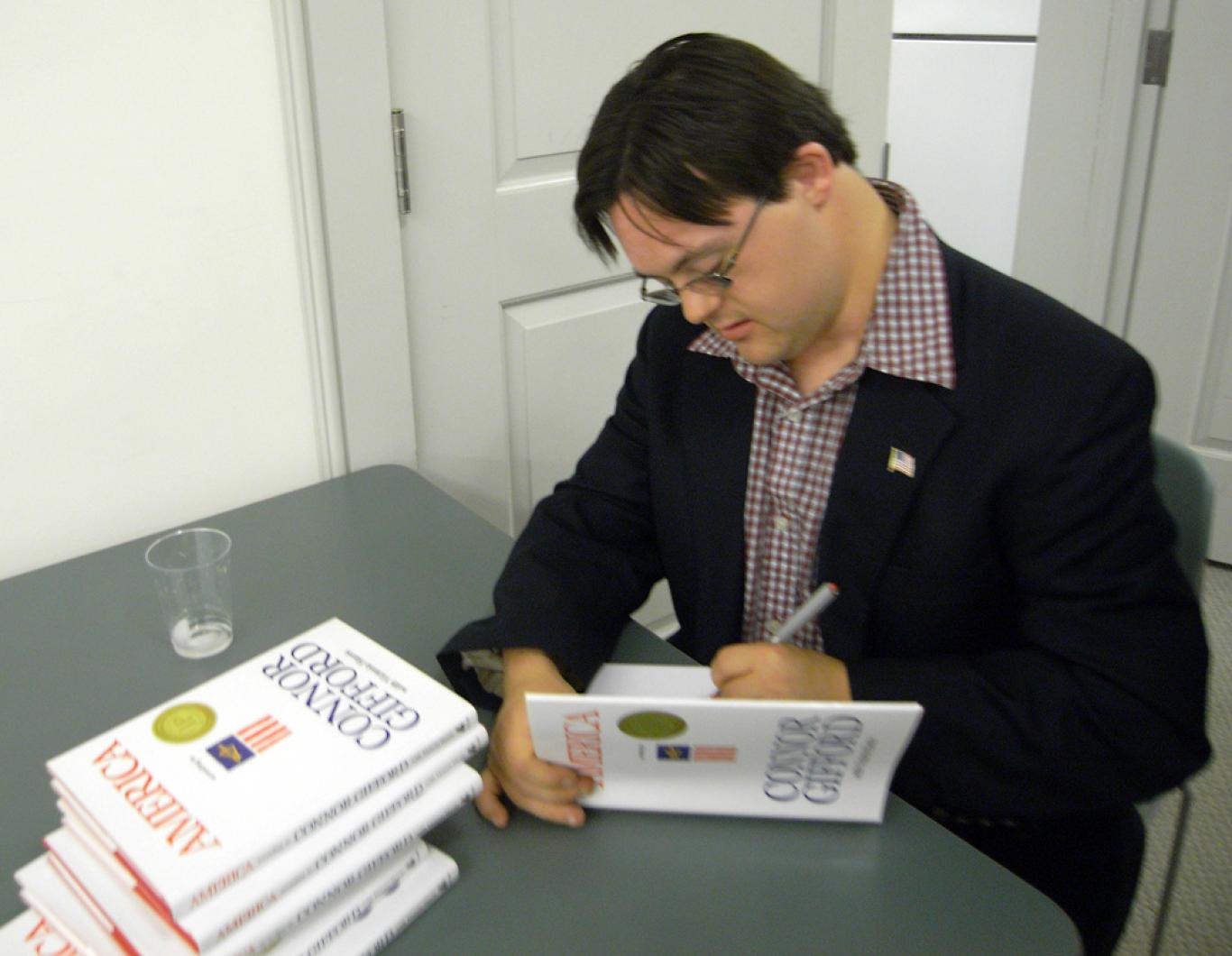

In the case of Connor Gifford, examples of the positive aspects of Down syndrome have been recorded in book form, giving a young man’s unique vision of the fables, foibles and fortune of the country he loves a place on the page.

Dressed in a dark, well-tailored suit complete with a well chosen, unassuming yet friendly necktie and obligatory American flag lapel pin, Mr. Gifford looked every bit the young politician as he took the podium in the basement of the Vineyard Haven library last Friday, May 7, to introduce himself and his book to a mostly-full room of Vineyarders. “Good afternoon, everyone . . . and thanks so much for joining me today so that I can share my story with you,” he said, eyes darting expertly between the notes on the podium in front of him and the audience around him.

America According to Connor Gifford is not rewriting what we as a nation think we know of our past, nor is it leveraging moments long gone for the purpose of promoting a particular viewpoint on contemporary issues. It stands, singularly, as a document that revisits myths of our nation, the moments in time that are referred to daily by pundits and professors, but only in passing or as points of comparison. These moments that so many have not given a thought to since high school civics class (if even then) are taken for granted as common knowledge.

However, this is not just a rehash of stories already told. Throughout Connor Gifford’s timeline of American history, some common threads emerge: people, by and large, are essentially good. Pain and suffering are bad, and when they occur, it is often via confusion or accident. Despite hiccups along the way, this nation has steadily grown to become more just, more free and more active in meeting the needs of not j ust its own citizens, but of everyone in the world.

To a news junkie or history buff, such a perspective would most likely be dismissed as narrow, naive, maybe nationalistic or perhaps even strange. But Mr. Gifford is neither ignorant nor avoidant of the bloody trials and shameful acts the country has suffered and committed, past and present. It’s just that his concept of America is, at its core, positive. And hopeful.

It is uncommon to find a person with Down syndrome who is able to read. And among the literate few, their interests tend to guide them towards image-dominated pop media or short, large-print children’s novels. Mr. Gifford not only reads, he reads without struggle, and voraciously. “He reads ad nauseum,” his mother states, with neither pride nor complaint. “Ever since the second grade.”

To read, let alone history books, let alone to write, is an uncommon passion for people with Down syndrome. But this rare hunger for the written word is possibly related to a rare subtype found in roughly 1 to 2 per cent of people with this already rare genetic condition. “He’s mosaic,” explains his mother, Julie Gifford. “I think it’s because of that that he’s really got an edge.”

Most people with Down syndrome have that third 21st chromosome present in every cell of their body. Mr. Gifford’s cells, however, are mixed: some have that third chromosome, and others do not. This subset of the syndrome is referred to as mosaiacism. The difference between mosaicism and “simple” Down syndrome, on a broader physiological level, are still being studied and not well understood. But many believe that having a mixed distribution of abnormal cell structures gives some individuals with the mosiac version of Down syndrome the mental “edge” to which Mr. Gifford’s mother is referring.

Regardless of terminology and medical specifics, when reading America According to Connor Gifford, one is nonetheless struck by two things: the positivity and hopefulness of his perspective, and the delightfully singular, strangely engrossing turns of phrase and placement of emphasis that show that not only is the author doing much more than running common knowledge through a filter of theory and academic insularity, but he is recalling, from his own mind, a vivid picture of the way things happened, always making sure to answer the question: Why?

And while the grammar school teachers who introduced us all to our nation’s past may have sometimes balked at that question, while our politicians may often toe the party line, and our pundits often make things up out of thin air for the sake of ratings, Mr. Gifford is not only unafraid to offer his own reasons: they tend to ring true in a way that is, just like everything else that helped bring this book into being, uncommon.

Comments

Comment policy »