On March 25, 1990, the call came over the marine radio channel 16. “This is the fishing vessel Sol e Mar,” said a frantic male voice. “We’re sinking. We need help now!” Then the line was cut and there was only static.

Coast Guard radio monitors on the Vineyard and Nantucket tried to raise the caller without success. A short time later another distress call came in, and this time caller was laughing.

Thinking now that the call was a hoax, the Coast Guard ended the matter.

The second call may indeed have been a hoax, but the first one was not, and next month marks the 20th anniversary of the tragic sinking of the Sol e Mar, captained by William Hokanson, 44, and his 19-year old son. The two men had gone out fishing for flounder off Noman’s Land three days earlier.

Today, thanks to the activation of new radio direction technology, tragedies like the sinking of Sol e Mar may disappear from the radar altogether.

Last October the Coast Guard flipped the switch on a computer-driven system that makes it easier to rescue a boater calling for help on VHF marine radio channel 16. The system is called Rescue 21.

For the Menemsha Coast Guard it is a major leap in technology. “It takes the search out of search and rescue,” said senior chief Stephen Barr in an interview at the station this week. While the technology is still being tested by all the Coast Guard stations in the region, Mr. Barr said the prospects for rescues in the future will be dramatically improved. The Coast Guard will now be able to dispatch help to a site as quickly as possible, with less emphasis on finding the site itself.

The radio system is based on real-time digital communication among six towers in southeastern New England, one of which is a newly installed 100-foot-plus tower on top of Peaked Hill in Chilmark. Peaked Hill is over 300 feet above sea level. With the help of data being exchanged between the towers, radio operators can pinpoint the location of a call for help nearly precisely, on water and on land.

The new system also is expected to dramatically reduce one of the biggest problems for the Coast Guard over the years: hoax calls. This is due to the ability precisely to locate the caller; many hoax calls originate inland and not on the water.

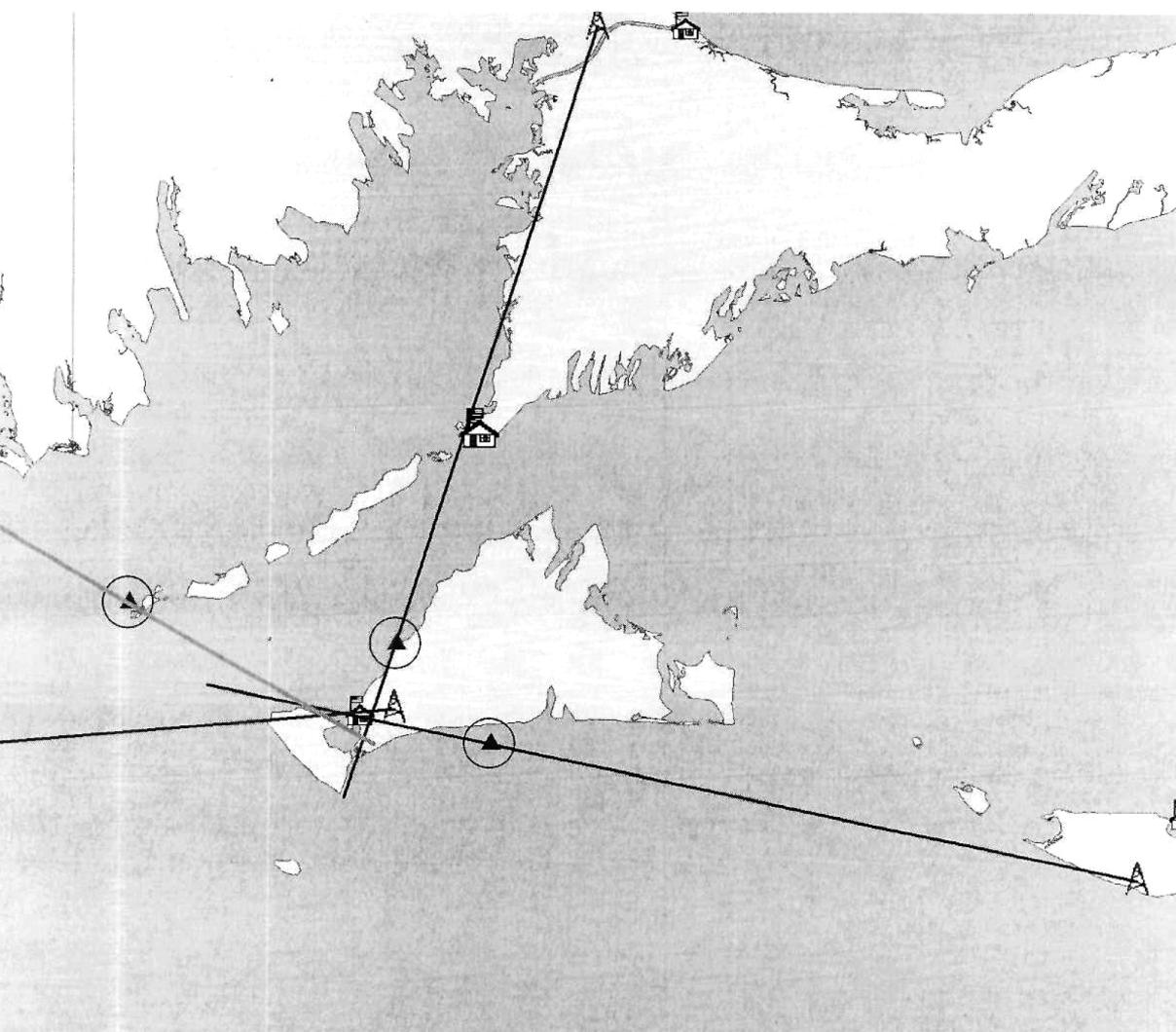

Seated in the radio room of the Menemsha Coast Guard Station this week, Mr. Barr and on-duty Coast Guard radio operator Shawne Dunbaugh looked at a computer screen. The screen showed all the waters around Cape Cod, the Vineyard and Nantucket down toward Rhode Island. Mr. Barr put his finger on each of the six antennas across the area, from Miacomet on Nantucket up to Provincetown on the Cape and west to Block Island.

If someone calls for help on marine radio channel 16, he said, it only takes two antennas to do the math and triangulate the place where the caller is located. Often more than two lines intersect the location. Anyone looking at the computer screen can tell almost precisely where a caller is located. The same screen is monitored by all the other Coast Guard stations in the area.

On this morning, Mr. Barr pointed to a fishing boat hailing from off Cape Cod. Two radio antennas pointed red lines at the caller.

Each morning, Mr. Barr said, the Menemsha Coast Guard station crew tests the system with their own marine radio. Radio antennas on Block Island, Nantucket and the Cape Cod Canal will point to the single caller at the Menemsha station.

“In the past, if we got a call for help, we’d have to search a 25-square-mile area of water. Now with this new system we probably only have to search a one-square-mile area,” the senior chief said.

The arrival of Rescue 21 comes almost exactly 20 years after the tragedy on the Sol e Mar, which became a national story of concern for safe boating.

The Rescue 21 Coast Guard literature is a memorial of sorts for the Sol e Mar, noting that the loss was the impetus for a concerted nationwide effort to upgrade Coast Guard search and rescue technology.

Capt. Bill (Hokey) Hokanson and his son William Jr. were flounder fishing eight miles south of Noman’s Land when they got into trouble. Four days after the calls came in and the Sol e Mar was reported missing, the Coast Guard recognized that the call from the Sol e Mar was not a hoax. A search was conducted, but it was too late.

The lost vessel was found by two divers two months later, seven and a half miles southeast of Noman’s Land.

The incident shook the maritime community, including the Coast Guard. Hearings were held in Woods Hole and eventually led to passage of the Studds Act, which made it a federal crime to make a hoax call and allowed the Coast Guard to acquire more search and rescue equipment.

Mark Forrest, chief of staff for Cong. Bill Delahunt and who formerly also worked for the late Cong. Gerry Studds, vividly recalled the Sol e Mar tragedy and the events that followed. “In the aftermath there were two responses. First, there was an increase in the fines for those who would commit a hoax. Before it was a slap on the wrist. The penalties were stiffened. And the second part was to provide greater technology to fill in the holes. We found there were gaps in coverage,” he said.

Mr. Forrest said Mr. Delahunt continues to push for legislation and money to keep the Coast Guard abreast of the ever-changing technology.

The search for John F. Kennedy Jr., his wife Carolyn Jeanne Bessette and a third person in the tragic plane crash south of the Vineyard in July of 1999 was made more difficult because of the prevailing radio “hole,” it was reported.

A boat explosion in Menemsha harbor in August of 1999 also showed a communications problem.

In October of 2001, ten years after the Sol e Mar incident, and two years after the Kennedy plane crash, a new 40-foot antenna was built atop Peaked Hill to serve the Coast Guard. It gave Menemsha and all the stations in the area better ears to monitor the waters south of the Vineyard and Noman’s Land. But the antenna was not good at pinpointing a caller’s location, and that is the value of Rescue 21.

Mr. Barr said there has been a huge technological jump in search and rescue since he joined the Coast Guard more than 20 years ago. He said even his crews aboard the station’s 47-foot motor life boat have access to a better radio direction finder than was used 20 years ago.

While the Rescue 21 system is still being tested, Mr. Barr said he expects it to be sensitive enough to put a location on a caller who is using a one-watt transmitter as far away as 20 miles.

Rescue 21 is being installed around the coastal United States and is not expected to be fully up and running until 2017. There are plans for it to operate in all 50 states, in the Great Lakes, along the nation’s many big rivers and as far away as Guam, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

So much has changed since the day the Sol e Mar went down. Fishing boats and most offshore boats are required to carry additional safety equipment. They carry EPIRB, an electronic emergency transmitter that when dropped into the water, or submerged, will automatically call for help and uses satellite technology.

Anyone purchasing a new VHF marine radio today will find that it includes a red button that when pushed triggers a distress call.

Mr. Dunbaugh, seated at a table with radios at the ready and computer screens showing images, said he was four years old when the Sol e Mar went down.

On Feb. 8, the Chilmark selectmen attended a meeting at the Menemsha station to see Rescue 21 in operation.

Mr. Barr said that when the Coast Guard finishes testing new technology and accepts it as fully operational, the old 40-foot antenna on Peaked Hill will be taken down. Final landscaping will be done around the new tower.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »