No one would call the new book Island Lives a rip-roaring read. Certainly not its authors, Allan R. Keith and Stephen A. Spongberg.

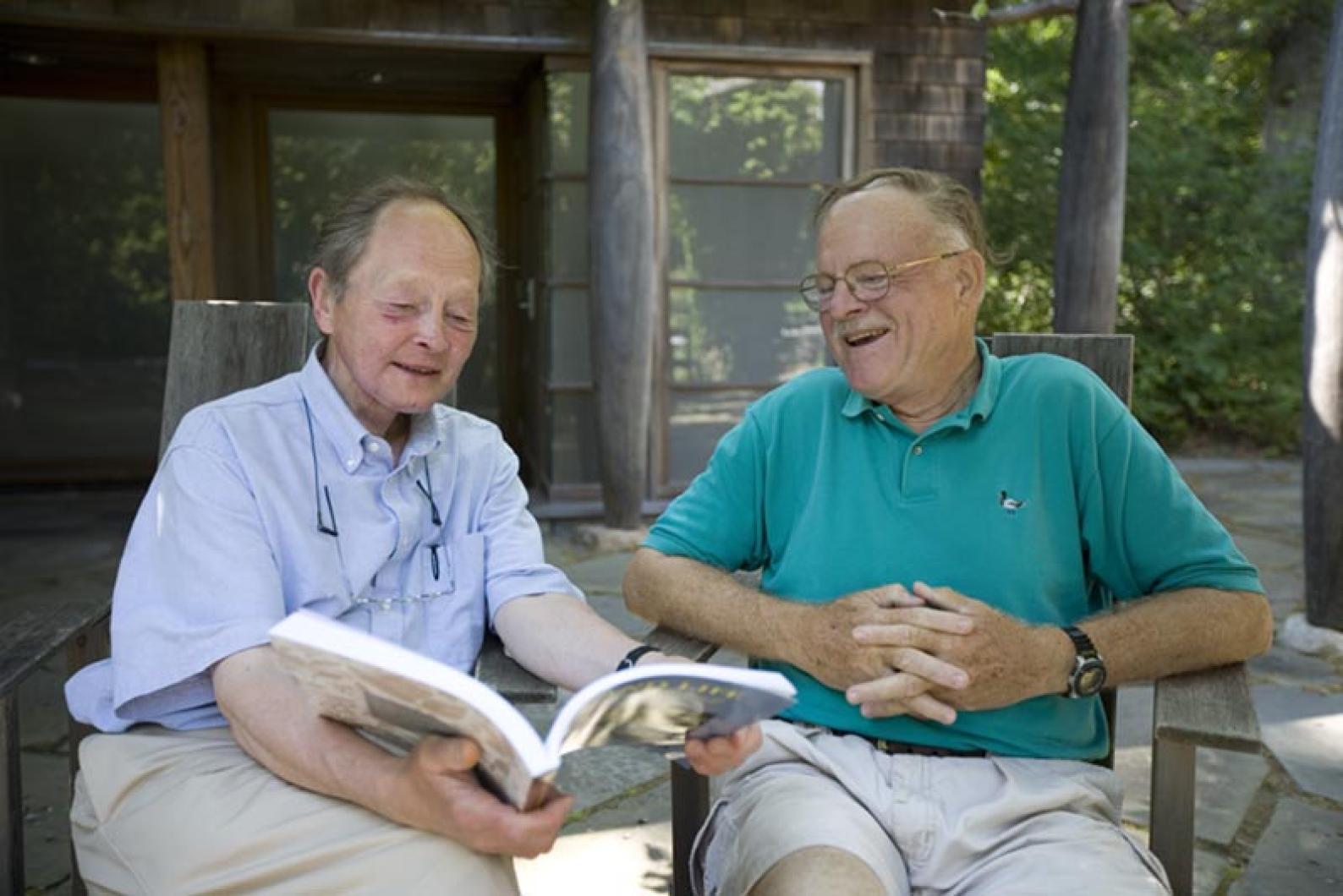

“It’s dry as toast,” said Mr Spongberg the other day, talking about it, sitting beneath the trees at Polly Hill Arboretum. “Dry as toast,” he repeated. “The bibliography is the most important part.”

That is not to say the authors are not passionate about their work. But the book is not exciting. It is sometimes fascinating, in an academic sort of way, but not exciting; about half its content is simply lists, and half of those lists are in Latin.

But it is nonetheless a bold venture, and a remarkable achievement. Drawing on their own expertise and the help of other experts, the two men set out to catalogue, as nearly as possible, all the living things on Martha’s Vineyard.

Indeed, they went beyond that. They also tried to catalogue the dead things whose remains turn up in the geological record of this place.

Now, you might think, after several hundred years of settlement, we might already have a pretty good fix on the Island’s biodiversity. And you might be wrong.

Take the bryophytes — mosses to most of us — for example. Before this book, said Mr. Keith, the most comprehensive list they could find contained 30 species.

Then the authors invited their collaborator Dr. Norton Miller, curator of bryology at the New York State Museum, to come down and take a look around.

“The number rose to 125, after three weekends,” said Mr. Keith.

It was a similar story, he said, when he decided with help from The Nature Conservancy’s Matt Pelikan to “take on” dragon and damsel flies.

“We more than doubled the number of species known on the Island, over the course of about five years,” he said.

Now, the thought of spending years cataloging dragonflies, mosses, slime molds, might not fill some people with enthusiasm. But Allan Keith and Stephen Spongberg are not such people.

“We had great fun because we started inviting knowledgeable people to come to the Vineyard and look at some of the life that had not been subject to much scrutiny,” said Mr. Spongberg.

“We spent hundreds of hours tramping the Vineyard. One of the fun parts is seeing how good your eye is.

“We hosted any number of people from the Boston Lichenological society. A good friend of mine is a moss person from the New York State Museum [Norton Miller]. We got to re-establish some friendships and make new friends.”

All the while “mining” the guests for their specialist knowledge.

The idea for the book was Mr. Keith’s. He is not by training a naturalist; he worked in investment management. But his “major avocation” was ornithology — he authored three books on birds of the West Indies.

He felt capable of cataloging the animal life of the Island, but not the botany. So his meeting with Mr. Spongberg at the arboretum about eight years ago — he had gone to see Polly Hill, but she wasn’t there — was fortuitous.

Mr. Spongberg, who had worked 28 years at Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, and was the founding director of the Polly Hill Arboretum.

“We discussed this very project,” said Mr. Keith. “It was then an idea for the future. That was in, maybe, 2000.

“We worked along over a number of years and then intensively two or three years ago after Steve retired.”

“In one little piece after another, things came together,” Mr. Keith said.

One of the biggest pieces was learning about the involvement of the Marine Biological Laboratories, Woods Hole, in an ambitious project called the Encyclopedia of Life (eol.org), which sets out to link databases all over the world to create a site which records, details and locates all life forms on the planet.

The EOL project — a little like Wikipedia — will rely heavily on content generated by so-called citizen scientists.

“One of the things the EOL is eventually going to be able to provide is an interactive site where you will be able to put in geographical co-ordinates, and out will come a list of everything known in that area,” said Mr. Keith.

The book is designed to be used in association with Internet-based resources. Thus there are no pictures of the 1,200-odd plants, 400 saltwater fish, 400 species of birds, et cetera, but there are references in the text to publications that provide illustrations, and an index of Web sites.

The book was published with the cooperation of MBL. They also got small grants from the Edey Foundation to research the life of Noman’s Land.

A condition of the grants was that copies of the book be given to the Island’s various conservation organizations, as well as schools and libraries.

The book will sell for $29.95 but was never meant to be a money-making venture. It is meant as a resource, and in many ways it is a collation and updating of the work of others. “We had a goal to assemble what is known as a baseline. Baselines are very important to scientific endeavor,” said Mr. Spongberg.

“This book has really been published to be picked apart, to be refined, added to, have deletions.

“It’s hopefully become a working manuscript, which over time will change in considerable way. We really wanted it to be a springboard...”

And, they admit, there are still gaps in the catalog. There is, said Mr. Keith, nothing at all on freshwater algae, or coral or sponges or annelid worms. They only got an estimated one-third of moth species and are less than comprehensive on other little things.

“Spiders for example,” said Mr. Keith. “There are many more species known from both Nantucket and the Falmouth area than there are on the Vineyard. There have to be close to 300 species here, but we only know about 80.” There is a request in the book that someone take on the task of cataloging them.

So, should you be looking for a new hobby . . . .

Comments

Comment policy »