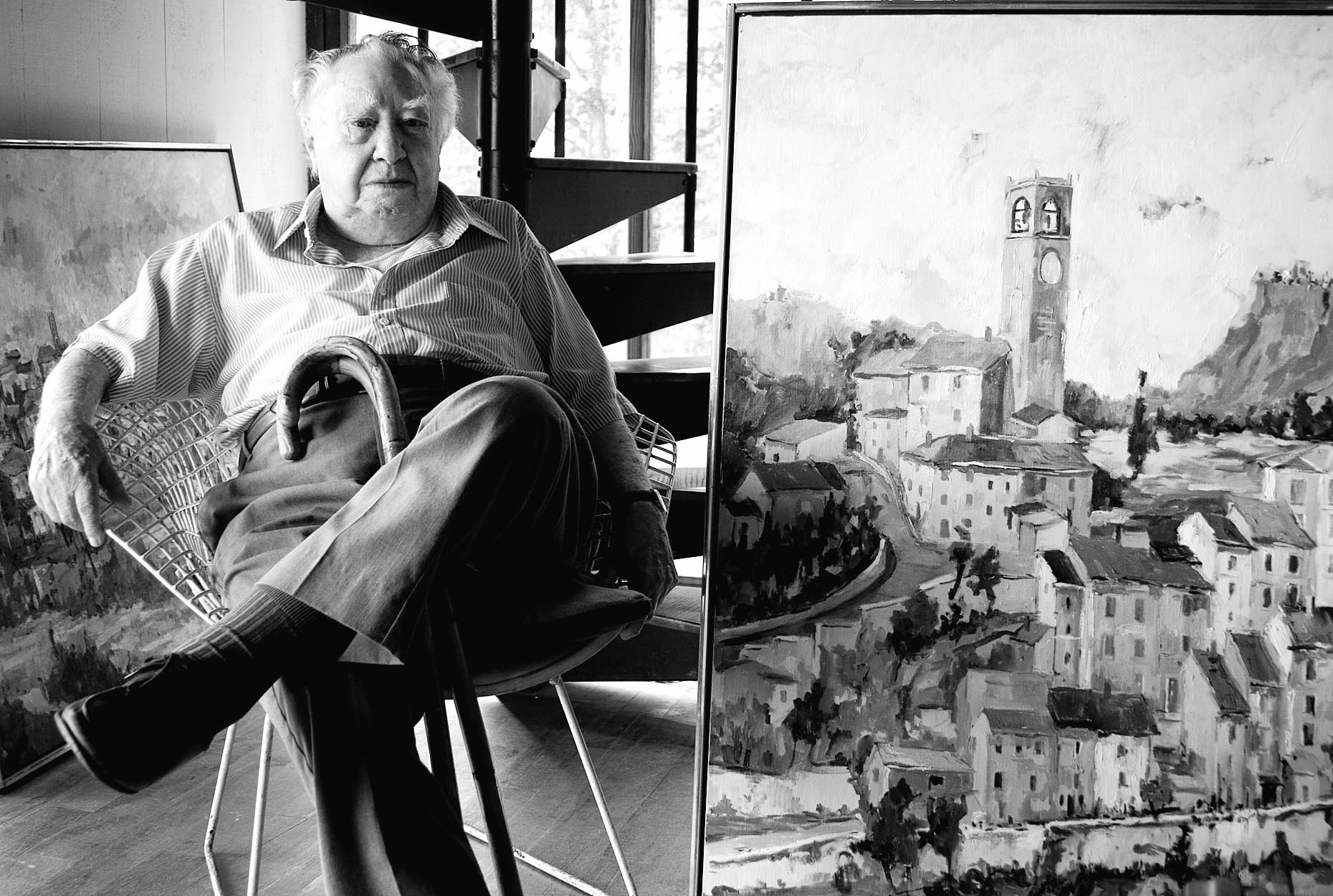

Albert Alcalay, oil painter, watercolorist, printmaker, sculptor, etcher, teacher of art and design and an Island seasonal resident since the 1960s, died March 29 in Boston of complications from an infection. He was 91 and made his winter home in Brookline.

In 1987 in a tribute for his 70th birthday, the late Angela Watson of West Tisbury, a longtime art educator at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, called Mr. Alcalay “a major force in contemporary art.” His work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Fogg Art Museum in Cambridge, the Museum of Modern Art in Rome, Colby College, Simmons College, Smith College and the University of Massachusetts, among others.

He had exhibited widely in galleries in New York city, Washington, D.C., Palo Alto, Calif., Paris, France, Vienna, Austria, Damascus, Syria, Beirut, Lebanon, and Pretoria, South Africa.

On the Vineyard, his work was shown at the late Virginia Berresford’s gallery in Menemsha, the Ford Gallery and the Field Gallery in West Tisbury, at the late Douglas Parker’s Vineyard Haven gallery and at the Lambert’s Cove home of Joshua and Lori Plaut. A pen and ink self portrait of Mr. Alcalay is in the permanent collection at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in Edgartown.

Mr. Alcalay and his wife Vera discovered the Vineyard in 1963, when David Douglas of West Tisbury — then one of Mr. Alcalay’s students of architectural design at Harvard, suggested they come to the Island on a visit.

“We had been spending our summers in Gloucester where Albert was teaching for many years. But the children were fed up with going to the beach with me every day. I wanted to show them Serbia, where I was born. Albert said he would only go to Europe to see churches. Then David Douglas proposed that we come to the Vineyard as a compromise. We did and Albert fell in love with the Island,” Mrs. Alcalay recalls.

The family first rented the George Brehm house on Music street in West Tisbury in 1963. They came that year with two children, four bicycles, a dog, a rabbit and a cat. Later they rented the Burton Engley house in Chilmark. Always devoted to music, Mr. Alcalay tended to play it loud and his wife remembers that sometimes the old house would shake from the sound.

Then in 1967 a story appeared in The New York Times indicating that Martha’s Vineyard was “the” place to go, Mr. Alcalay told Brooks Robards in an interview for the Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, and the Alcalays decided it was time for them to buy an Island home of their own.

“My wife and I looked and looked, but we could not afford anything, so David said ‘I’ll sell you some land for virtually nothing if you will let me build the house,’ but I told him I didn’t have the money,“ Mr. Alcalay recalled in the interview.

“Then one day,” Vera Alcalay recalls, “Albert called David about something and was told he wasn’t available.

“He’s building your house,” Albert was told.

“We still didn’t know how we could afford it. But Albert had a one-man show just then that took up three floors of the De Cordova Museum in Lincoln and he sold enough to pay for the house.

“ ‘I never doubted that you’d be able to buy it,’ ” she remembers David Douglas saying of the Campbell Road home in West Tisbury that he, Allan Miller and the late Bronislaw Lesnikowki built for the Alcalays. The weathered shingle house blends unobtrusively into the woods in which it is set.

“That was 1968 and we have summered there every year since until last year,” Mrs. Alcalay said. The combination of rheumatoid arthritis which affected Mr. Alcalay’s legs and macular degeneration, which had affected his eyes, forced them to remain in Brookline.

In a studio behind the Campbell Road house, or more recently, in a studio upstairs in the house, Mr. Alcalay, who loved the art of painting, would tirelessly work each day during the summer months. He said of his work that it was not descriptive but evocative.

“The painting does not tell the onlooker the whole story. The other part he must supply with his own imagination,” he told Cooper Davis in a Gazette interview two years ago. Lori Plaut, the owner of numerous Alcalay works, reiterates that.

“One day when we were about to have a show of his work, I went to his house to pick up the paintings. There was one there that he urged me to take. It was of a road with a lot of movement in it and vivid colors, but something about it bothered me and I really didn’t want it in the show. But I finally took it anyway because he was so insistent, and I own it now.

“Albert explained to me that ordinarily he considered a road a protagonist, but that the road in this painting was like moving flames. It represented fear — the fear he had felt fleeing the Holocaust, and it was that that had been gnawing at me,” Mrs. Plaut said.

Mr. Alcalay always liked painting in bright colors. He told a Boston Globe interviewer in 2004: “Color is part of my circulation, I think I would use red even if I were in the North Pole where everything is white.” The Globe called his work “vibrant.”

He said his painting was a reflection of his joyful outlook on life. Although he painted each day, in Brookline as well as on the Vineyard, he also took time to enjoy himself. A chocolate bomb at the Black Dog, an ice cream cone at Mad Martha’s or a fine, lengthy European-style meal at his friend Mitzi Pratt’s in Aquinnah were always satisfying rewards for a day of painting.

Ever gregarious, he was sure to find time to visit with friends. A spellbinding storyteller, he would recount how he had escaped in the 1940s from the Nazis in Serbia in what was then Yugoslavia and escaped them again in Italy. He recalled those years in his book of last year, The Persistance of Memory that can be found in the West Tisbury Library.

Albert Alcalay was born in Paris in 1917, a son of the late Samuel and Lepa Afar Alcalay. On the eve of the outbreak of World War I, his banker father had been moved from Belgrade to Paris, but when the war ended, the family returned to Belgrade. There, young Alcalay attended secondary school, was apprenticed to an artist, was active in Jewish youth groups and began studies in architecture. But he was dreaming of going to Palestine to work on a collective farm when World War II started and he went into the Yugoslavian army.

It was not long before he was a prisoner of war, but — miraculously — he was able to talk his way to freedom. The German general in charge of the camp, as he described it in his book, “seemed to be a decent man . . . . He had known life before Hitler . . . . I was convinced that he valued human dignity, and that ultimately he was a man of religion . . . . I made my way to his office . . . . I told the general that I was a young artist and an architect, that I was planning to do a lot with my life, and that I had a family and a girlfriend . . . . I told him I had high ambitions for my art . . . . I pleaded that no one had anything to gain by shipping me to a concentration camp . . . .

“ ‘All right. Go home,’ he said . . . . But I was at the gates just ready to leave . . . when he arrived. He shook my hand . . . and told me ‘Do not think that I like Jews. I only admired your desire to live and your civil courage,’ ”

Later in the war, he forged the documents of an Italian citizen and escaped to Italy, but when his false documents were recognized as such, he was sent to a concentration camp. The rest of his family was already there, it turned out.

Also among his fellow prisoners was the German Expressionist painter Michael Fingesten, whose work young Alcalay had long admired and who offered to instruct him in portrait painting.

When the Germans began to insist that the Italians start persecuting the Jews as they were, the Alcalays were fortunate enough to have a sympathetic local postmistress warn them that a telegram had arrived saying that they were to be sent to Dachau.

“Within minutes,” Albert Alcalay remembered in a 1987 Gazette interview, “the family Alcalay was off and running, to hide in the mountains from the Nazis.”

For the next two years they fled from farmhouse barn to monastery to farmhouse barn managing to elude the Germans. Finally, at war’s end, the Alcalays settled in Rome where Albert began painting frantically — and selling well. Then in 1951 a break came when the family became the beneficiaries of a bill offered by President Truman to displaced persons. It enabled Albert and Vera — whom he met in Rome and who was then his wife — his parents and his sister to come to the United States.

A year later, at his wife’s suggestion, the Alcalays settled in Brookline. Mr. Alcalay, however, made frequent weekend train trips to New York to absorb — and to paint — the city. The urban paintings he did were notable for their absence of people.

“His work presents a jetsream vision moving across urban terrain at high altitude, watching the landscape spread out, rotate and recede,” art critic Robert Taylor wrote in the Boston Globe. The energy of the cities was largely what he was painting until his best friend died unexpectedly. As a way of coping with his loss, Mr. Alcalay began to paint a six-foot square canvas furiously. When he was finished, the painting he had produced was a landscape filled with hills, fields, ponds and sky, and he realized that landscape was an important part of his painting too.

He had his first solo show in Boston in 1952 at the Swetzoff Gallery. In 1959, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship and in 1960 began lecturing in visual arts at Harvard. He was among the founders of Harvard’s School of Visual and Environmental Studies. Although he retired in 1982, he continued as an extension school lecturer for a number of years. He was also a visiting lecturer at the University of Maryland. Students remember him for his captivating lecture style.

But over the last seven years, as his eyesight failed, he no longer would cope with the large canvases. Instead, he largely painted smaller scale watercolors, quipping that his work was being done in his macular degeneration style. He put spaces between the colors because he could not see where they met. He also painted on vellum. Sometimes in these watercolors, he remembered the Italian countryside of his youth. Sometimes he painted Vineyard landscapes.

In recent Island summers, he has had to be less active than in the past, when he would eagerly take house guests to see his favorite gingerbread houses in the Oak Bluffs Camp Ground, or go to the Gay Head Cliffs or Menemsha for painting inspiration. Taking it easy, he and his wife would drive to Farm Neck for lunch or out to East Chop or West Chop. On Sundays, however, he often visited Island art openings as he always had. He visited the Polly Hill Arboretum with Mitzi Pratt and, though he could barely see, remarked on how thoughtfully the plantings had been broken up by texture. “He was always such a joy to be with,” she remembers.

Over the years, his art became more and more abstract and he began doing sculpture as well as drawing and painting. “He liked to call himself an abstract expressionist,” his wife said, but she pointed out that he was also an expert at drawing. He frequently did drawings in India ink on rice paper.

Mr. Alcalay was a man of many languages, as well as many kinds of art and was fluent in Serbian, Italian, French, English and Hebrew. He also — though he did not like it — knew some German.

“He was truly a Renaissance man,” Lori Plaut says.

A few years ago, some of his devoted former students did a documentary of his life that they called Albert Alcalay: Portrait of an Artist.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Alcalay is survived by two sons, Leor of Brookline, and Ammiel of Brooklyn, N.Y.; a sister, Buena Alcalay Pearlman of Newton Center, two grandsons and a granddaughter.

Comments (4)

Comments

Comment policy »